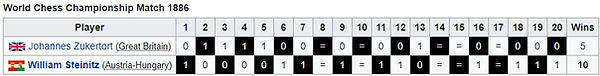

The full World Championship match results:

Get rythm (Joaquin Phoenix / Johnny Cash)

Hey get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

Get a rock and roll feelin' in your bones

Get taps on your toes and get gone

Get rhythm when you get the blues

A little shoeshine boy he never gets lowdown

But he's got the dirtiest job in town

Bendin' low at the people's feet

On a windy corner of a dirty street

Well I asked him while he shined my shoes

How'd he keep from gettin' the blues

He grinned as he raised his little head

He popped his shoeshine rag and then he said

Get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

Yes a jumpy rhythm makes you feel so fine

It'll shake all your troubles from your worried mind

Get rhythm when you get the blues

Get rhythm when you get the blues

Get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

Get a rock and roll feelin' in your bones

Get taps on your toes and get gone

Get rhythm when you get the blues

Well I sat and listened to the sunshine boy

I thought I was gonna jump with joy

He slapped on the shoe polish left and right

He took his shoeshine rag and he held it tight

He stopped once to wipe the sweat away

I said you mighty little boy to be a workin' that way

He said I like it with a big wide grin

Kept on a poppin' and he'd say it again

Get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

It only cost a dime just a nickel a shoe

It does a million dollars worth of good for you

Get rhythm when you get the blues

For the good times (Kris Kristofferson)

Don't look so sad. I know it's over

But life goes on and this world keeps on turning

Let's just be glad we had this time to spend together

There is no need to watch the bridges that we're burning

Lay your head upon my pillow

Hold your warm and tender body close to mine

Hear the whisper of the raindrops

Blow softly against my window

Make believe you love me one more time

For the good times

I'll get along; you'll find another,

And I'll be here if you should find you ever need me.

Don't say a word about tomorrow or forever,

There'll be time enough for sadness when you leave me.

Lay your head upon my pillow

Hold your warm and tender body Close to mine

Hear the whisper of the raindrops

Blow softly against my window

Make believe you love me

One more time

For the good times

STABELVOLLEN MEDIA

Copyright of all music videoes, guest photoes and artworks solely belongs to the artists. Copyright of all other resources : Stabelvollen Media.

CHESS WORLD CHAMPIONS 1886 - 1927

Source: FIDE. 2020.

1. VILHELM STEINITZ

Wilhelm (later William) Steinitz (May 17, 1836 – August 12, 1900) was an Austrian and later American chess master, and the first undisputed World Chess Champion, from 1886 to 1894. He was also a highly influential writer and chess theoretician.

When discussing chess history from the 1850s onwards, commentators have debated whether Steinitz could be effectively considered the champion from an earlier time, perhaps as early as 1866. Steinitz lost his title to Emanuel Lasker in 1894, and lost a rematch in 1896–97.

Statistical rating systems give Steinitz a rather low ranking among world champions, mainly because he took several long breaks f from competitive play. However, an analysis based on one of these rating systems shows that he was one of the most dominant players in the history of the game. Steinitz was unbeaten in match play for 32 years, from 1862 to 1894.

Although Steinitz became "world number one" by winning in the all-out attacking style that was common in the 1860s, he unveiled in 1873 a new positional style of play, and demonstrated that it was superior to the previous style. His new style was controversial and some even branded it as "cowardly", but many of Steinitz's games showed that it could also set up attacks as ferocious as those of the old school.

Steinitz was also a prolific writer on chess, and defended his new ideas vigorously. The debate was so bitter and sometimes abusive that it became known as the "Ink War". Steinitz was the target of anti-Semitic abuse,[citation needed] and moved to the United States in 1883 to escape this. By the early 1890s, Steinitz's approach was widely accepted, and the next generation of top players acknowledged their debt to him, most notably his successor as world champion, Emanuel Lasker.

Early life

Steinitz was born on May 17, 1836, in Prague (now capital of the Czech Republic; then in Bohemia, a part of the Austrian Empire). The youngest of a tailor's thirteen sons to survive, he learned to play chess at age 12. He began playing serious chess in his twenties, after leaving Prague in 1857 to study mathematics in Vienna,[1] at the Vienna Polytechnic. Steinitz spent two years at the university.

Chess career (through 1881)

Steinitz improved rapidly in chess during the late 1850s, progressing from third place in the 1859 Vienna City championship to first in 1861, with a score of 30/31. During this period he was nicknamed "the Austrian Morphy". his achievement meant that he had become the strongest player in Austria.[6]

International debut

Steinitz in 1866

Steinitz was then sent to represent Austria in the London 1862 chess tournament. He placed sixth, but his win over Augustus Mongredien was awarded the tournament's brilliancy prize.[7][unreliable source] He immediately challenged the fifth-placed contestant, the strong veteran Italian Master Serafino Dubois, to a match, which Steinitz won (five wins, one draw, three losses).[4] This encouraged him to turn professional, and he took up residence in London.[6] In 1862–63 Steinitz scored a crushing win in a match with Joseph Henry Blackburne, who went on to be one of the world's top ten for 20 years, but who had only started playing chess two years earlier.[8] Steinitz then beat some leading UK players in matches: Frederic Deacon and Augustus Mongredien in 1863, and Valentine Green in 1864.[9] This charge up the rankings had a price: in March 1863 Steinitz apologized in a letter to Ignác Kolisch for not repaying a loan, because while Steinitz had been beating Blackburne, Daniel Harrwitz had "taken over" all of Steinitz's clients at the London Chess Club, who had provided Steinitz's main source of income.[10]

Match against Anderssen

Adolf Anderssen was recognized as the world's top player until 1866, when Steinitz won a match against him.

These successes established Steinitz as one of the world's top players, and he was able to arrange a match in 1866 in London against Adolf Anderssen, who was regarded as the world's strongest active player because he had won the 1851 and 1862 London International Tournaments and his one superior, Paul Morphy, had retired from competitive chess. Steinitz won with eight wins and six losses (there were no draws), but it was a hard fight; after 12 games the scores were level at 6–6, then Steinitz won the last two games.

As a result of this match victory, Steinitz was generally regarded as the world's best player. The prize money for this match was £100 to the winner (Steinitz) and £20 for the loser (Anderssen). The winner's prize was a large sum by the standards of the times, equivalent to about £57,500 in 2007's mone.

Continued match play success

In the years following his victory over Anderssen, Steinitz beat Henry Bird in 1866 (seven wins, five losses, five draws). He comfortably beat Johannes Zukertort in 1872 (seven wins, four draws, one loss; Zukertort had proved himself one of the elite by beating Anderssen by a large margin in 1871).

Gradually improves tournament results

It took longer for Steinitz to reach the top in tournament play. In the next few years he took: third place at Paris 1867 behind Ignatz Kolisch and Simon Winawer; and second place at Dundee (1867; Gustav Neumann won), and Baden-Baden 1870 chess tournament; behind Anderssen but ahead of Blackburne, Louis Paulsen and other strong players. His first victory in a strong tournament was London 1872, ahead of Blackburne and Zukertort; and the first tournament in which Steinitz finished ahead of Anderssen was Vienna 1873, when Anderssen was 55 years old.

Changes style, introduces positional school

All of Steinitz's successes up to 1872 were achieved in the attack-at-all-costs "Romantic" style exemplified by Anderssen. But in the Vienna 1873 chess tournament, Steinitz unveiled a new "positional" style of play which was to become the basis of modern chess. He tied for first place with Blackburne, ahead of Anderssen, Samuel Rosenthal, Paulsen and Henry Bird, and won the play-off against Blackburne. Steinitz made a shaky start, but won his last 14 games in the main tournament (including 2–0 results over Paulsen, Anderssen, and Blackburne) plus the two play-off games – this was the start of a 25-game winning streak in serious competition.

Hiatus from competitive chess

Between 1873 and 1882 Steinitz played no tournaments and only one match (a 7–0 win against Blackburne in 1876). His other games during this period were in simultaneous and blindfold exhibitions, which contributed an important part of a professional chess-player's income in those days (for example in 1887 Blackburne was paid 9 guineas for two simultaneous exhibitions and a blindfold exhibition hosted by the Teesside Chess Association; this was equivalent to about £4,800 at 2007 values).

Early life

Steinitz was born on May 17, 1836, in Prague (now capital of the Czech Republic; then in Bohemia, a part of the Austrian Empire). The youngest of a tailor's thirteen sons to survive, he learned to play chess at age 12. He began playing serious chess in his twenties, after leaving Prague in 1857 to study mathematics in Vienna, at the Vienna Polytechnic. Steinitz spent two years at the university.

Chess career (through 1881)

Steinitz improved rapidly in chess during the late 1850s, progressing from third place in the 1859 Vienna City championship to first in 1861, with a score of 30/31.During this period he was nicknamed "the Austrian Morphy". This achievement meant that he had become the strongest player in Austria

International debut

Steinitz in 1866

Steinitz was then sent to represent Austria in the London 1862 chess tournament. He placed sixth, but his win over Augustus Mongredien was awarded the tournament's brilliancy prize.[7][unreliable source] He immediately challenged the fifth-placed contestant, the strong veteran Italian Master Serafino Dubois, to a match, which Steinitz won (five wins, one draw, three losses).[4] This encouraged him to turn professional, and he took up residence in London.[6] In 1862–63 Steinitz scored a crushing win in a match with Joseph Henry Blackburne, who went on to be one of the world's top ten for 20 years, but who had only started playing chess two years earlier.[8] Steinitz then beat some leading UK players in matches: Frederic Deacon and Augustus Mongredien in 1863, and Valentine Green in 1864.[9] This charge up the rankings had a price: in March 1863 Steinitz apologized in a letter to Ignác Kolisch for not repaying a loan, because while Steinitz had been beating Blackburne, Daniel Harrwitz had "taken over" all of Steinitz's clients at the London Chess Club, who had provided Steinitz's main source of income.[10]

Match against Anderssen

Adolf Anderssen was recognized as the world's top player until 1866, when Steinitz won a match against him.

These successes established Steinitz as one of the world's top players, and he was able to arrange a match in 1866 in London against Adolf Anderssen, who was regarded as the world's strongest active player because he had won the 1851 and 1862 London International Tournaments and his one superior, Paul Morphy, had retired from competitive chess. Steinitz won with eight wins and six losses (there were no draws), but it was a hard fight; after 12 games the scores were level at 6–6, then Steinitz won the last two games.

As a result of this match victory, Steinitz was generally regarded as the world's best player. The prize money for this match was £100 to the winner (Steinitz) and £20 for the loser (Anderssen). The winner's prize was a large sum by the standards of the times, equivalent to about £57,500 in 2007's money.

Continued match play success

In the years following his victory over Anderssen, Steinitz beat Henry Bird in 1866 (seven wins, five losses, five draws). He comfortably beat Johannes Zukertort in 1872 (seven wins, four draws, one loss; Zukertort had proved himself one of the elite by beating Anderssen by a large margin in 1871)

Gradually improves tournament results

It took longer for Steinitz to reach the top in tournament play. In the next few years he took: third place at Paris 1867 behind Ignatz Kolisch and Simon Winawer; and second place at Dundee (1867; Gustav Neumann won), and Baden-Baden 1870 chess tournament; behind Anderssen but ahead of Blackburne, Louis Paulsen and other strong players. His first victory in a strong tournament was London 1872, ahead of Blackburne and Zukertort; and the first tournament in which Steinitz finished ahead of Anderssen was Vienna 1873, when Anderssen was 55 years old.

Changes style, introduces positional school

All of Steinitz's successes up to 1872 were achieved in the attack-at-all-costs "Romantic" style exemplified by Anderssen. But in the Vienna 1873 chess tournament, Steinitz unveiled a new "positional" style of play which was to become the basis of modern chess. He tied for first place with Blackburne, ahead of Anderssen, Samuel Rosenthal, Paulsen and Henry Bird, and won the play-off against Blackburne. Steinitz made a shaky start, but won his last 14 games in the main tournament (including 2–0 results over Paulsen, Anderssen, and Blackburne[9]) plus the two play-off games – this was the start of a 25-game winning streak in serious competition.

Hiatus from competitive chess

Between 1873 and 1882 Steinitz played no tournaments and only one match (a 7–0 win against Blackburne in 1876). His other games during this period were in simultaneous and blindfold exhibitions,[7][unreliable source] which contributed an important part of a professional chess-player's income in those days (for example in 1887 Blackburne was paid 9 guineas for two simultaneous exhibitions and a blindfold exhibition hosted by the Teesside Chess Association; this was equivalent to about £4,800 at 2007 values).

World Championship match

Eventually it was agreed that in 1886 Steinitz and Zukertort would play a match in New York, St. Louis and New Orleans, and that the victor would be the player who first won 10 games. At Steinitz's insistence the contract said it would be "for the Championship of the World". After the five games played in New York, Zukertort led by 4–1, but in the end Steinitz won decisively by 12½–7½ (ten wins, five draws, five losses). The collapse by Zukertort, who won only one of the last 15 games, has been described as "perhaps the most thoroughgoing reversal of fortune in the history of world championship play."

Though not yet officially an American citizen, Steinitz wanted the United States flag to be placed next to him during the match. He became a US citizen on November 23, 1888, having resided for five years in New York, and changed his first name from Wilhelm to William.

In 1887 the American Chess Congress started work on drawing up regulations for the future conduct of world championship contests. Steinitz actively supported this endeavor, as he thought he was becoming too old to remain world champion – he wrote in his own magazine "I know I am not fit to be the champion, and I am not likely to bear that title for ever".

Defeats Chigorin

In 1888 the Havana Chess Club offered to sponsor a match between Steinitz and whomever he would select as a worthy opponent. Steinitz nominated the Russian Mikhail Chigorin, on the condition that the invitation should not be presented as a challenge from him. There is some doubt about whether this was intended to be a match for the world championship: both Steinitz's letters and the publicity material just before the match conspicuously avoided the phrase. The proposed match was to have a maximum of 20 games, and Steinitz had said that fixed-length matches were unsuitable for world championship contests because the first player to take the lead could then play for draws; and Steinitz was at the same time supporting the American Chess Congress's world championship project.Whatever the status of the match, it was played in Havana in January to February 1889, and won by Steinitz (ten wins, one draw, six losses).

New York 1889 tournament

The American Chess Congress's final proposal was that the winner of a tournament to be held in New York in 1889 should be regarded as world champion for the time being, but must be prepared to face a challenge from the second or third placed competitor within a month Steinitz wrote that he would not play in the tournament and would not challenge the winner unless the second and third placed competitors failed to do so. The tournament was duly played, but the outcome was not quite as planned: Mikhail Chigorin and Max Weiss tied for first place; their play-off resulted in four draws, and Weiss then wanted to get back to his work for the Rothschild Bank, conceding the title to Chigorin.

However, the third prize-winner Isidor Gunsberg was prepared to play for the title. The match was played in New York in 1890 and ended in a 10½–8½ victory for Steinitz. The American Chess Congress's experiment was not repeated, and Steinitz's last three matches were private arrangements between the players.

Wins rematch against Chigorin

In 1891 the Saint Petersburg Chess Society and the Havana Chess Club offered to organize another Steinitz–Chigorin match for the world championship. Steinitz played against Chigorin in Havana in 1892, and won narrowly (ten wins, five draws, eight losses).

German Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch turned down an opportunity in 1892 to challenge Steinitz in a world championship match, because of the demands of his medical practice.

Loses title to Lasker

Around this time Steinitz publicly spoke of retiring, but changed his mind when Emanuel Lasker, 32 years younger and comparatively untested at the top level, challenged him. Lasker had been earlier that year refused a non-title challenge by fellow German, Dr. Siegbert Tarrasch, who was at the time the world's most dominant tournament player.

Initially, Lasker wanted to play for $5,000 a side, and a match was agreed at stakes of $3,000 a side, but Steinitz agreed to a series of reductions when Lasker found it difficult to raise the money, and the final figure was $2,000 each, which was less than for some of Steinitz's earlier matches (the final combined stake of $4,000 would be worth about $114,000 at 2016 values). Although this was publicly praised as an act of sportsmanship on Steinitz's part Steinitz may have desperately needed the money.

The match was played in 1894, at venues in New York, Philadelphia and Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The 32-year age difference between the combatants was the largest in the history of world championship play, and remains so today.[35] Steinitz had previously declared he would win without doubt, so it came as a shock when Lasker won the first game. Steinitz responded by winning the second, and was able to maintain the balance until the sixth. However, Lasker won all the games from the seventh to the 11th, and Steinitz asked for a one-week rest. When the match resumed, Steinitz looked in better shape and won the 13th and 14th games. Lasker struck back in the 15th and 16th, and Steinitz was unable to compensate for his losses in the middle of the match. Hence Lasker won with ten wins, five losses and four draws.Some commentators thought Steinitz's habit of playing "experimental" moves in serious competition was a major factor in his downfall.

Increased tournament activity

After losing the title, Steinitz played in tournaments more frequently than he had previously. He won at New York 1894, and was fifth at Hastings 1895 (winning the first brilliancy prize for his game with Curt von Bardeleben). At Saint Petersburg 1895, a super-strong four player, multi-round-robin event, with Lasker, Chigorin and Pillsbury, he took second place behind Lasker. Later his results began to decline: 6th in Nuremberg 1896, 5th in Cologne 1898, 10th in London 1899.

In early 1896, Steinitz defeated the Russian Emanuel Schiffers in a match (winning 6 games, drawing 1, losing 4).

Outclassed in rematch with Lasker

In November, 1896 to January, 1897 Steinitz played a return match with Lasker in Moscow, but won only 2 games, drawing 5, and losing 10. This was the last world chess championship match for eleven years. Shortly after the match, Steinitz had a mental breakdown and was confined for 40 days in a Moscow sanatorium, where he played chess with the inmates.

Influence on the game

Steinitz's play up to and including 1872 was similar to that of his contemporaries: sharp, aggressive, and full of sacrificial play. This was the style in which he became "world number one" by beating Adolf Anderssen in 1866 and confirmed his position by beating Zukertort in 1872 and winning the 1872 London International tournament (Zukertort had claimed the rank of number two by beating Anderssen in 1871).

In 1873, however, Steinitz's play suddenly changed, giving priority to what is now called the positional elements in chess: pawn structure, space, outposts for knights, the advantage of the two bishops, etc. Although Steinitz often accepted unnecessarily difficult defensive positions in order to demonstrate the superiority of his theories, he also showed that his methods could provide a platform for crushing attacks. Steinitz's successor as world champion, Emanuel Lasker, summed up the new style as: "In the beginning of the game ignore the search for combinations, abstain from violent moves, aim for small advantages, accumulate them, and only after having attained these ends search for the combination – and then with all the power of will and intellect, because then the combination must exist, however deeply hidden."

Although Steinitz's play changed abruptly, he said he had been thinking along such lines for some years:

Some of the games which I saw Paulsen play during the London Congress of 1862 gave a still stronger start to the modification of my own opinions, which has since developed, and I began to recognize that Chess genius is not confined to the more or less deep and brilliant finishing strokes after the original balance of power and position has been overthrown, but that it also requires the exercise of still more extraordinary powers, though perhaps of a different kind to maintain that balance or respectively to disturb it at the proper time in one's own favor.

During his nine-year layoff from tournament play (1873–1882) and later in his career, Steinitz used his chess writings to present his theories – while in the UK he wrote for The Field; in 1885 after moving to New York he founded the "International Chess Magazine", of which he was the chief editor; and in 1889 he edited the book of the great New York 1889 tournament (won by Mikhail Chigorin and Max Weiss),[59] in which he did not compete as the tournament was designed to produce his successor as World Champion. Many other writers found his new approach incomprehensible, boring or even cowardly; for example Adolf Anderssen said, "Kolisch is a highwayman and points the pistol at your breast. Steinitz is a pick-pocket, he steals a pawn and wins a game with it."

But when he contested the first World Championship match in 1886 against Johannes Zukertort, it became evident that Steinitz was playing on another level. Although Zukertort was at least Steinitz's equal in spectacular attacking play, Steinitz often outmaneuvered him fairly simply by the use of positional principles.

By the time of his match in 1890–91 against Gunsberg, some commentators showed an understanding of and appreciation for Steinitz's theories. Shortly before the 1894 match with Emanuel Lasker, even the New York Times, which had earlier published attacks on his play and character, paid tribute to his playing record, the importance of his theories, and his sportsmanship in agreeing to the most difficult match of his career despite his previous intention of retiring.

By the end of his career, Steinitz was more highly esteemed as a theoretician than as a player. The comments about him in the book of the Hastings 1895 chess tournament focus on his theories and writings, and Emanuel Lasker was more explicit: "He was a thinker worthy of a seat in the halls of a University. A player, as the world believed he was, he was not; his studious temperament made that impossible; and thus he was conquered by a player ..."

As a result of his play and writings Steinitz, along with Paul Morphy, is considered by many chess commentators to be the founder of modern chess.Lasker, who took the championship from Steinitz, wrote, "I who vanquished him must see to it that his great achievement, his theories should find justice, and I must avenge the wrongs he suffered." Vladimir Kramnik emphasizes Steinitz's importance as a pioneer in the field of chess theory: "Steinitz was the first to realise that chess, despite being a complicated game, obeys some common principles. ... But as often happens the first time is just a try. ... I can't say he was the founder of a chess theory. He was an experimenter and pointed out that chess obeys laws that should be considered."

Playing strength and style

Statistical rating systems are unkind to Steinitz. "Warriors of the Mind" gives him a ranking of 47th, below several obscure Soviet grandmasters; Chessmetrics places him only 15th on its all-time list. Chessmetrics penalizes players who play infrequently;opportunities for competitive chess were infrequent in Steinitz's best years, and Steinitz had a few long absences from competitive play (1873–1876, 1876–1882, 1883–1886, 1886–1889). However, in 2005 Chessmetrics' author, Jeff Sonas, wrote an article which examined various ways of comparing the strength of "world number one" players, using data provided by Chessmetrics, and found that: Steinitz was further ahead of his contemporaries in the 1870s than Bobby Fischer was in his peak period (1970–1972); that Steinitz had the third-highest total number of years as the world's top player, behind Emanuel Lasker and Garry Kasparov; and that Steinitz placed 7th in a comparison of how long players were ranked in the world's top three. Between his victory over Anderssen (1866) and his loss to Emanuel Lasker (1894), Steinitz won all his "normal" matches, sometimes by wide margins; and his worst tournament performance in that 28-year period was third place in Paris (1867).(He also lost two handicap matches and a match by telegraph in 1890 against Mikhail Chigorin, where Chigorin was allowed to choose the openings in both games and won both.)

Initially Steinitz played in the all-out attacking style of contemporaries like Anderssen, and then changed to the positional style with which he dominated competitive chess in the 1870s and 1880s. Max Euwe wrote, "Steinitz aimed at positions with clear-cut features, to which his theory was best applicable." However, he retained his capacity for brilliant attacks right to the end of his career; for example in the 1895 Hastings tournament (when he was 59) he beat von Bardeleben in a spectacular game in which in the closing stages Steinitz deliberately exposed all his pieces to attack simultaneously (except his king, of course). His most significant weaknesses were his habits of playing "experimental" moves and getting into unnecessarily difficult defensive positions in top-class competitive games.

First Chess World Championship 1886 Steinitz - Zuckertort. Steinitz's blunder in Round 4

The World Championship had these results in game 1 to game 3:

Game 1: Zukertort–Steinitz, 0–1

Game 2: Steinitz–Zukertort, 0–1

Game 3: Zukertort–Steinitz, 1–0

In game 4 the draws leading up to draw 37, were:1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 Nf6 4.0–0 Nxe4 5.Re1 Nd6 6.Nxe5 Nxe5 7.Rxe5+ Be7 8.Bf1 0–0 9.d4 Bf6 10.Re1 Re8 11.c3 Rxe1 12.Qxe1 Nf5 13.Bf4 d6 14.Nd2 Be6 15.Bd3 Nh4 16.Ne4 Ng6 17.Bd2 d5 18.Nc5 Bc8 19.Qe3 b6 20.Nb3 Qd6 21.Qe8+ Nf8 22.Re1 Bb7 23.Qe3 Ne6 24.Qf3 Rd8 25.Qf5 Nf8 26.Bf4 Qc6 27.Nd2 Bc8 28.Qh5 g6 29.Qe2 Ne6 30.Bg3 Qb7 31.Nf3 c5 32.dxc5 bxc5 33.Ne5 c4 34.Bb1 Bg7 35.Rd1 Bd7 36.Qf3 Be8. The diagram to the left shows the position after 36 draws.

Then in draw 37 Steinitz blundered capturing the pawn on c4 with the knight on e5:

37. Nxc4.

Steinitz's idea seemed to be fine: The knight on c4 could not be captured by the pawn on d5, since the

Queens then are opposing in the diagonal f3 - b7.

But this was the blunder, Zukertort actually could capture the knight, and he did!

37. dxc4.

What was it that Steinitz had overlooked?

Probably not that if the queen on f3 captures the black queen on b7, then the rook on d8

checkmates with Rxd1.

But maybe that the queen on b7 can be defended by the knight on e6 cpturing on d8 after Rxd8:

38. Rxd8 Nxd8

After 39. Qe2 Ne6 Steinitz reseigned.

The full game:

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 Nf6 4.0–0 Nxe4 5.Re1 Nd6 6.Nxe5 Nxe5 7.Rxe5+ Be7 8.Bf1 0–0 9.d4 Bf6 10.Re1 Re8 11.c3 Rxe1 12.Qxe1 Nf5 13.Bf4 d6 14.Nd2 Be6 15.Bd3 Nh4 16.Ne4 Ng6 17.Bd2 d5 18.Nc5 Bc8 19.Qe3 b6 20.Nb3 Qd6 21.Qe8+ Nf8 22.Re1 Bb7 23.Qe3 Ne6 24.Qf3 Rd8 25.Qf5 Nf8 26.Bf4 Qc6 27.Nd2 Bc8 28.Qh5 g6 29.Qe2 Ne6 30.Bg3 Qb7 31.Nf3 c5 32.dxc5 bxc5 33.Ne5 c4 34.Bb1 Bg7 35.Rd1 Bd7 36.Qf3 Be8 37.Nxc4?? dxc4 38.Rxd8 Nxd8 39.Qe2 Ne6 0–1.

The full World Championship match results:

2. EMANUEL LASKER

Emanuel Lasker (December 24, 1868 – January 11, 1941) was a German chess player, mathematician, and philosopher who was World Chess Champion for 27 years, from 1894 to 1921, the longest reign of any officially r recognised World Chess Champion in history. In his prime, Lasker was one of the most dominant champions, and he is still generally regarded as one of the strongest players ever.

His contemporaries used to say that Lasker used a "psychological" approach to the game, and even that he sometimes deliberately played inferior moves to confuse opponents. Recent analysis, however, indicates that he was ahead of his time and used a more flexible approach than his contemporaries, which mystified many of them. Lasker knew contemporary analyses of openings well but disagreed with many of them. He published chess magazines and five chess books, but later players and commentators found it difficult to draw lessons from his methods.

Lasker made contributions to the development of other games. He was a first-class contract bridge player[1] and wrote about bridge, Go, and his own invention, Lasca. His books about games presented a problem that is still considered notable in the mathematical analysis of card games. Lasker was a research mathematician who was known for his contributions to commutative algebra, which included proving the primary decomposition of the ideals of polynomial rings. His philosophical works and a drama that he co-wrote, however, received little attention.

Early years 1868–1894

Emanuel Lasker was born on December 24, 1868, at Berlinchen in Neumark (now Barlinek in Poland), the son of a Jewish cantor. At the age of eleven he was sent to Berlin to study mathematics, where he lived with his brother Berthold, eight years his senior, who taught him how to play chess. Berthold was among the world's top ten players in the early 1890s.To supplement their income Emanuel Lasker played chess and card games for small stakes, especially at the Café Kaiserhof.

Lasker won the Café Kaiserhof's annual Winter tournament 1888/89 and the Hauptturnier A ("second division" tournament) at the sixth DSB Congress (German Chess Federation's congress) held in Breslau. Winning the Hauptturnier earned Lasker the title of "master". The candidates were divided into two groups of ten. The top four in each group competed in a final. Lasker won his section, with 2½ points more than his nearest rival. However, scores were reset to 0 for the final. With two rounds to go, Lasker trailed the leader, Viennese amateur von Feierfeil, by 1½ points. Lasker won both of his final games, while von Feierfeil lost in the penultimate round (being mated in 121 moves after the position was reconstructed incorrectly following an adjournment) and drew in the last round. The two players were now tied. Lasker won a playoff and garnered the master title. This enabled him to play in master-level tournaments and thus launched his chess career.

Lasker finished second in an international tournament at Amsterdam, ahead of Mason and Gunsberg. In spring 1892, he won two tournaments in London, the second and stronger of these without losing a game. At New York City 1893, he won all thirteen games, one of the few times in chess history that a player has achieved a perfect score in a significant tournament.

His record in matches was equally impressive: at Berlin in 1890 he drew a short play-off match against his brother Berthold; and won all his other matches from 1889 to 1893, mostly against top-class opponents: Curt von Bardeleben (1889), Jacques Mieses (1889), Henry Edward Bird (1890), Berthold Englisch (1890), Joseph Henry Blackburne (1892), Jackson Showalter (1892–93) and Celso Golmayo Zúpide (1893). Chessmetrics calculates that Emanuel Lasker became the world's strongest player in mid-1890, and that he was in the top ten from the very beginning of his recorded career in 1889.

In 1892 Lasker founded the first of his chess magazines, The London Chess Fortnightly, which was published from August 15, 1892 to July 30, 1893. In the second quarter of 1893 there was a gap of ten weeks between issues, allegedly because of problems with the printer. Shortly after its last issue Lasker traveled to the US, where he spent the next two years.

Lasker challenged Siegbert Tarrasch, who had won three consecutive strong international tournaments (Breslau 1889, Manchester 1890, and Dresden 1892), to a match. Tarrasch haughtily declined, stating that Lasker should first prove his mettle by attempting to win one or two major international events.

Chess competition 1894–1918

Matches against Steinitz

Wilhelm Steinitz, whom Lasker beat in World Championship matches in 1894 and 1896

Rebuffed by Tarrasch, Lasker challenged the reigning World Champion Wilhelm Steinitz to a match for the title. Initially Lasker wanted to play for US$5,000 a side and a match was agreed at stakes of $3,000 a side, but Steinitz agreed to a series of reductions when Lasker found it difficult to raise the money. The final figure was $2,000, which was less than for some of Steinitz's earlier matches (the final combined stake of $4,000 would be worth over $495,000 at 2006 values). Although this was publicly praised as an act of sportsmanship on Steinitz's part, Steinitz may have desperately needed the money. The match was played in 1894, at venues in New York, Philadelphia, and Montreal. Steinitz had previously declared he would win without doubt, so it came as a shock when Lasker won the first game. Steinitz won the second game, and maintained the balance through the sixth. However, Lasker won all the games from the seventh to the eleventh, and Steinitz asked for a week's rest. When the match resumed, Steinitz looked in better shape and won the 13th and 14th games. Lasker struck back in the 15th and 16th, and Steinitz did not compensate for his losses in the middle of the match. Hence Lasker won convincingly with ten wins, five losses and four draws. Lasker thus became the second formally recognized World Chess Champion, and confirmed his title by beating Steinitz even more convincingly in their re-match in 1896–97 (ten wins, two losses, and five draws).

Tournament successes

Influential players and journalists belittled the 1894 match both before and after it took place. Lasker's difficulty in getting backing may have been caused by hostile pre-match comments from Gunsberg and Leopold Hoffer, who had long been a bitter enemy of Steinitz. One of the complaints was that Lasker had never played the other two members of the top four, Siegbert Tarrasch and Mikhail Chigorin – although Tarrasch had rejected a challenge from Lasker in 1892, publicly telling him to go and win an international tournament first.After the match, some commentators, notably Tarrasch, said Lasker had won mainly because Steinitz was old (58 in 1894).

Emanuel Lasker answered these criticisms by creating an even more impressive playing record. He came third at Hastings 1895 (where he may have been suffering from the after-effects of typhoid fever), behind Pillsbury and Chigorin but ahead of Tarrasch and Steinitz; then won first prizes at very strong tournaments in St Petersburg 1895–96 (an elite, 4-player tournament; ahead of Steinitz, Pillsbury and Chigorin), Nuremberg (1896), London (1899) and Paris (1900); tied for second at Cambridge Springs 1904, and tied for first at the Chigorin Memorial in St Petersburg 1909.

Later, at St Petersburg (1914), he overcame a 1½-point deficit to finish ahead of the rising stars, Capablanca and Alexander Alekhine, who later became the next two World Champions. For decades chess writers have reported that Tsar Nicholas II of Russia conferred the title of "Grandmaster of Chess" upon each of the five finalists at St Petersburg 1914 (Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Tarrasch and Marshall), but chess historian Edward Winter has questioned this, stating that the earliest known sources supporting this story were published in 1940 and 1942.

Matches against Marshall and Tarrasch

Main articles: World Chess Championship 1907 and World Chess Championship 1908

Lasker's match record was as impressive between his 1896–97 re-match with Steinitz and 1914: he won all but one of his normal matches, and three of those were convincing defenses of his title.

In 1906 Lasker and Géza Maróczy agreed to terms for a World Championship, but the arrangements could not be finalised, and the match never took place.

Lasker's first world championship match since 1897 was against Frank Marshall in the World Chess Championship 1907. Despite his aggressive style, Marshall could not win a single game, losing eight and drawing seven (final score: 11½−3½).

He then played Tarrasch in the World Chess Championship 1908, first at Düsseldorf then at Munich. Tarrasch firmly believed the game of chess was governed by a precise set of principles. For him the strength of a chess move was in its logic, not in its efficiency. Because of his stubborn principles he considered Lasker as a coffeehouse player who won his games only thanks to dubious tricks, while Lasker mocked the arrogance of Tarrasch who, in his opinion, shone more in salons than at the chessboard. At the opening ceremony, Tarrasch refused to talk to Lasker, only saying: "Mr. Lasker, I have only three words to say to you: check and mate!"

Tarrasch vs. Lasker,

World Championship 1908

Lasker gave a brilliant answer on the chessboard, winning four of the first five games, and playing a type of chess Tarrasch could not understand. For example, in the second game after 19 moves arose a situation (see diagram) in which Lasker was a pawn down, with a bad bishop and doubled pawns. At this point it appeared Tarrasch was winning, but 20 moves later he was forced to resign. Lasker eventually won by 10½−5½ (eight wins, five draws, and three losses). Tarrasch claimed

the wet weather was the cause of his defeat.

Matches against Janowski

World Chess Championship 1910 (Lasker–Janowski)

In 1909 Lasker drew a short match (two wins, two losses) against Dawid Janowski, an all-out attacking Polish expatriate. Several months later they played a longer match in Paris, and chess historians still debate whether this was for the World Chess Championship. Understanding Janowski's style, Lasker chose to defend solidly so that Janowski unleashed his attacks too soon and left himself vulnerable. Lasker easily won the match 8–2 (seven wins, two draws, one loss). This victory was convincing for everyone but Janowski, who asked for a revenge match. Lasker accepted and they played a World Chess Championship match in Berlin in November–December 1910. Lasker crushed his opponent, winning 9½−1½ (eight wins, three draws, no losses). Janowski did not understand Lasker's moves, and after his first three losses he declared to Edward Lasker, "Your homonym plays so stupidly that I cannot even look at the chessboard when he thinks. I am afraid I will not do anything good in this match."

Match against Schlechter

World Chess Championship 1910 (Lasker–Schlechter)

Schlechter would have taken Lasker's world title if he had won or drawn the last game of their 1910 match.

Between his two matches against Janowski, Lasker arranged another World Chess Championship in January–February 1910 against Carl Schlechter. Schlechter was a modest gentleman, who was generally unlikely to win the major chess tournaments by his peaceful inclination, his lack of aggressiveness and his willingness to accept most draw offers from his opponents (about 80% of his games finished by a draw).

At the beginning, Lasker tried to attack but Schlechter had no difficulty defending, so that the first four games finished in draws. In the fifth game Lasker had a big advantage, but committed a blunder that cost him the game. Hence at the middle of the match Schlechter was one point ahead. The next four games were drawn, despite fierce play from both players. In the sixth Schlechter managed to draw a game being a pawn down. In the seventh Lasker nearly lost because of a beautiful exchange sacrifice from Schlechter. In the ninth only a blunder from Lasker allowed Schlechter to draw a lost ending. The score before the last game was thus 5–4 for Schlechter. In the tenth game Schlechter tried to win tactically and took a big advantage, but he missed a clear win at the 35th move, continued to take increasing risks and finished by losing. Hence the match was a draw and Lasker remained World Champion.

It has been speculated that Schlechter played unusually risky chess in the tenth game because the terms of the match required him to win by a margin of two games. But according to Isaak and Vladimir Linder, this was unlikely. The match was originally to be a 30-game affair and Schlechter would have to win by two games. But they note that according to the Austrian chess historian Michael Ehn, Lasker agreed to forgo the plus two provision in view of the match being subsequently reduced to only 10 games. For proof Ehn quoted Schlechter's comment printed in Allgemeine Sportzeitung (ASZ) of December 9, 1909 "There will be ten games in all. The winner on points will receive the title of world champion. If the points are equal, the decision will be made by the arbiter."

Abandoned challenges

In 1911 Lasker received a challenge for a world title match against the rising star José Raúl Capablanca. Lasker was unwilling to play the traditional "first to win ten games" type of match in the semi-tropical conditions of Havana, especially as drawn games were becoming more frequent and the match might last for over six months. He therefore made a counter-proposal: if neither player had a lead of at least two games by the end of the match, it should be considered a draw; the match should be limited to the best of thirty games, counting draws; except that if either player won six games and led by at least two games before thirty games were completed, he should be declared the winner; the champion should decide the venue and stakes, and should have the exclusive right to publish the games; the challenger should deposit a forfeit of US$2,000 (equivalent to over $250,000 in 2020 values); the time limit should be twelve moves per hour; play should be limited to two sessions of 2½ hours each per day, five days a week. Capablanca objected to the time limit, the short playing times, the thirty-game limit, and especially the requirement that he must win by two games to claim the title, which he regarded as unfair. Lasker took offence at the terms in which Capablanca criticized the two-game lead condition and broke off negotiations, and until 1914 Lasker and Capablanca were not on speaking terms. However, at the 1914 St. Petersburg tournament, Capablanca proposed a set of rules for the conduct of World Championship matches, which were accepted by all the leading players, including Lasker.

Late in 1912 Lasker entered into negotiations for a world title match with Akiba Rubinstein, whose tournament record for the previous few years had been on a par with Lasker's and a little ahead of Capablanca's. The two players agreed to play a match if Rubinstein could raise the funds, but Rubinstein had few rich friends to back him and the match was never played. This situation demonstrated some of the flaws inherent in the championship system then being used. The start of World War I in summer 1914 put an end to hopes that Lasker would play either Rubinstein or Capablanca for the World Championship in the near future. Throughout World War I (1914–1918) Lasker played in only two serious chess events. He convincingly won (5½−½) a non-title match against Tarrasch in 1916. In September–October 1918, shortly before the armistice, he won a quadrangular (four-player) tournament, half a point ahead of Rubinstein.

Academic activities 1894–1918

David Hilbert encouraged Lasker to obtain a Ph.D in mathematics.

Despite his superb playing results, chess was not Lasker's only interest. His parents recognized his intellectual talents, especially for mathematics, and sent the adolescent Emanuel to study in Berlin (where he found he also had a talent for chess). Lasker gained his abitur (high school graduation certificate) at Landsberg an der Warthe, now a Polish town named Gorzów Wielkopolski but then part of Prussia. He then studied mathematics and philosophy at the universities in Berlin, Göttingen (where David Hilbert was one of his doctoral advisors) and Heidelberg.

In 1895 Lasker published two mathematical articles in Nature. On the advice of David Hilbert he registered for doctoral studies at Erlangen during 1900–1902.In 1901 he presented his doctoral thesis Über Reihen auf der Convergenzgrenze ("On Series at Convergence Boundaries") at Erlangen and in the same year it was published by the Royal Society. He was awarded a doctorate in mathematics in 1902. His most significant mathematical article, in 1905, published a theorem of which Emmy Noether developed a more generalized form, which is now regarded as of fundamental importance to modern algebra and algebraic geometry.

Lasker held short-term positions as a mathematics lecturer at Tulane University in New Orleans (1893) and Victoria University in Manchester (1901; Victoria University was one of the "parents" of the current University of Manchester). However, he was unable to secure a longer-term position, and pursued his scholarly interests independently.

In 1906 Lasker published a booklet titled Kampf (Struggle), in which he attempted to create a general theory of all competitive activities, including chess, business and war. He produced two other books which are generally categorized as philosophy, Das Begreifen der Welt (Comprehending the World; 1913) and Die Philosophie des Unvollendbar (sic; The Philosophy of the Unattainable; 1918).

Other activities 1894–1918

In 1896–97 Lasker published his book Common Sense in Chess, based on lectures he had given in London in 1895.

In 1903, Lasker played in Ostend against Mikhail Chigorin, a six-game match that was sponsored by the wealthy lawyer and industrialist Isaac Rice in order to test the Rice Gambit. Lasker narrowly lost the match. Three years later Lasker became secretary of the Rice Gambit Association, founded by Rice in order to promote the Rice Gambit, and in 1907 Lasker quoted with approval Rice's views on the convergence of chess and military strategy.

In November 1904, Lasker founded Lasker's Chess Magazine, which ran until 1909.

For a short time in 1906 Emanuel Lasker was interested in the strategy game Go, but soon returned to chess. He was introduced to the game by his namesake Edward Lasker, who wrote a successful book Go and Go-Moku in 1934.

At the age of 42, in July 1911, Lasker married Martha Cohn (née Bamberger), a rich widow who was a year older than Lasker and already a grandmother. They lived in Berlin. Martha Cohn wrote popular stories under the pseudonym "L. Marco".

During World War I, Lasker invested all of his savings in German war bonds, which lost nearly their entire value with the wartime and post-war inflation. During the war, he wrote a pamphlet which claimed that civilization would be in danger if Germany lost the war.

Match against Capablanca. World Chess Championship 1921

In January 1920 Lasker and José Raúl Capablanca signed an agreement to play a World Championship match in 1921, noting that Capablanca was not free to play in 1920. Because of the delay, Lasker insisted on a final clause that allowed him to play anyone else for the championship in 1920, that nullified the contract with Capablanca if Lasker lost a title match in 1920, and that stipulated that if Lasker resigned the title Capablanca should become World Champion. Lasker had previously included in his agreement before World War I to play Akiba Rubinstein for the title a similar clause that if he resigned the title, it should become Rubinstein's.

A report in the American Chess Bulletin (July–August 1920 issue) said that Lasker had resigned the world title in favor of Capablanca because the conditions of the match were unpopular in the chess world. The American Chess Bulletin speculated that the conditions were not sufficiently unpopular to warrant resignation of the title, and that Lasker's real concern was that there was not enough financial backing to justify his devoting nine months to the match. When Lasker resigned the title in favor of Capablanca he was unaware that enthusiasts in Havana had just raised $20,000 to fund the match provided it was played there. When Capablanca learned of Lasker's resignation he went to the Netherlands, where Lasker was living at the time, to inform him that Havana would finance the match. In August 1920 Lasker agreed to play in Havana, but insisted that he was the challenger as Capablanca was now the champion. Capablanca signed an agreement that accepted this point, and soon afterwards published a letter confirming this. Lasker also stated that, if he beat Capablanca, he would resign the title so that younger masters could compete for it.

The match was played in March–April 1921. After four draws, the fifth game saw Lasker blunder with Black in an equal ending. Capablanca's solid style allowed him to easily draw the next four games, without taking any risks. In the tenth game, Lasker as White played a position with an isolated queen pawn but failed to create the necessary activity and Capablanca reached a superior ending, which he duly won. The eleventh and fourteenth games were also won by Capablanca, and Lasker resigned the match.

Reuben Fine and Harry Golombek attributed this to Lasker's being in mysteriously poor form.[4][74] On the other hand, Vladimir Kramnik thought that Lasker played quite well and the match was an "even and fascinating fight" until Lasker blundered in the last game, and explained that Capablanca was 20 years younger, a slightly stronger player, and had more recent competitive practice.

Return to the United States and death

In August 1937, Martha and Emanuel Lasker decided to leave the Soviet Union, and they moved, via the Netherlands, to the United States (first Chicago, next New York) in October 1937.They were visiting Martha's daughter, but they may also have been motivated by political upheaval in the Soviet Union. In the United States Lasker tried to support himself by giving chess and bridge lectures and exhibitions, as he was now too old for serious competition. In 1940 he published his last book, The Community of the Future, in which he proposed solutions for serious political problems, including anti-Semitism and unemployment.

Lasker died of a kidney infection in New York on January 11, 1941, at the age of 72, as a charity patient at the Mount Sinai Hospital. He was buried at historic Beth Olom Cemetery, Queens, New York. His wife Martha and his sister, Mrs. Lotta Hirschberg, survived him.

Assessment

Playing strength and style

Lasker was considered to have a "psychological" method of play in which he considered the subjective qualities of his opponent, in addition to the objective requirements of his position on the board. Richard Réti published a lengthy analysis of Lasker's play in which he concluded that Lasker deliberately played inferior moves that he knew would make his opponent uncomfortable. W. H. K. Pollock commented, "It is no easy matter to reply correctly to Lasker's bad moves."

Lasker himself denied the claim that he deliberately played bad moves, and most modern writers agree. According to Grandmaster Andrew Soltis and International Master John L. Watson, the features that made his play mysterious to contemporaries now appear regularly in modern play: the g2–g4 "Spike" attack against the Dragon Sicilian;[citation needed] sacrifices to gain positional advantage; playing the "practical" move rather than trying to find the best move; counterattacking and complicating the game before a disadvantage became serious. Former World Champion Vladimir Kramnik said, "He realized that different types of advantage could be interchangeable: tactical edge could be converted into strategic advantage and vice versa", which mystified contemporaries who were just becoming used to the theories of Steinitz as codified by Siegbert Tarrasch.

Max Euwe opined that the real reason behind Lasker's success was his "exceptional defensive technique" and that "almost all there is to say about defensive chess can be demonstrated by examples from the games of Steinitz and Lasker", with the former exemplifying passive defence and the latter an active defence.

The famous win against José Raúl Capablanca at St. Petersburg in 1914, which Lasker needed in order to retain any chance of catching up with Capablanca, is sometimes offered as evidence of his "psychological" approach. Reuben Fine describes Lasker's choice of opening, the Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez, as "innocuous but psychologically potent". However, an analysis of Lasker's use of this variation throughout his career concludes that he had excellent results with it as White against top-class opponents, and sometimes used it in "must-win" situations. Luděk Pachman writes that Lasker's choice presented his opponent with a dilemma: with only a ½ point lead, Capablanca would have wanted to play safe; but the Exchange Variation's pawn structure gives White an endgame advantage, and Black must use his bishop pair aggressively in the middlegame to nullify this. In Kramnik's opinion, Lasker's play in this game demonstrated deep positional understanding, rather than psychology.

Fine reckoned Lasker paid little attention to the openings, but Capablanca thought Lasker knew the openings very well but disagreed with a lot of contemporary opening analysis. In fact before the 1894 world title match, Lasker studied the openings thoroughly, especially Steinitz's favorite lines. He played primarily e4 openings, particularly the Ruy Lopez. He opened with 1.d4 relatively rarely, although his d4 games had a higher winning percentage than his e4 ones. With the Black pieces, he mainly answered 1.e4 with the French Defense and 1.d4 with the Queen's Gambit. Lasker also used the Sicilian Defense fairly often. In Capablanca's opinion, no player surpassed Lasker in the ability to assess a position quickly and accurately, in terms of who had the better prospects of winning and what strategy each side should adopt. Capablanca also wrote that Lasker was so adaptable that he played in no definite style, and that he was both a tenacious defender and a very efficient finisher of his own attacks.

Lasker followed Steinitz's principles, and both demonstrated a completely different chess paradigm than the “romantic” mentality before them. Thanks to Steinitz and Lasker, positional players gradually became common (Tarrasch, Schlechter, and Rubinstein stand out.) But, while Steinitz created a new school of chess thought, Lasker's talents were far harder for the masses to grasp; hence there was no Lasker school.

In addition to his enormous chess skill, Lasker was said to have an excellent competitive temperament: his rival Siegbert Tarrasch once said, "Lasker occasionally loses a game, but he never loses his head." Lasker enjoyed the need to adapt to varying styles and to the shifting fortunes of tournaments. Although very strong in matches, he was even stronger in tournaments. For over 20 years, he always finished ahead of the younger Capablanca: at St. Petersburg 1914, New York 1924, Moscow 1925, and Moscow 1935.Only in 1936 (15 years after their match), when Lasker was 67, did Capablanca finish ahead of him.

In 1964, Chessworld magazine published an article in which future World Champion Bobby Fischer listed the ten greatest players in history. Fischer did not include Lasker in the list, deriding him as a "coffee-house player [who] knew nothing about openings and didn't understand positional chess". In a poll of the world's leading players taken some time after Fischer's list appeared, Tal, Korchnoi, and Robert Byrne all said that Lasker was the greatest player ever.Both Pal Benko and Byrne stated that Fischer later reconsidered and said that Lasker was a great player.

Statistical ranking systems place Lasker high among the greatest players of all time. The book Warriors of the Mind places him sixth, behind Garry Kasparov, Anatoly Karpov, Fischer, Mikhail Botvinnik and Capablanca. In his 1978 book The Rating of Chessplayers, Past and Present, Arpad Elo gave retrospective ratings to players based on their performance over the best five-year span of their career. He concluded that Lasker was the joint second strongest player of those surveyed (tied with Botvinnik and behind Capablanca). The most up-to-date system, Chessmetrics, is rather sensitive to the length of the periods being compared, and ranks Lasker between fifth and second strongest of all time for peak periods ranging in length from one to twenty years. Its author, the statistician Jeff Sonas, concluded that only Kasparov and Karpov surpassed Lasker's long-term dominance of the game. By Chessmetrics' reckoning, Lasker was the number 1 player in 292 different months—a total of over 24 years. His first No. 1 rank was in June 1890, and his last in December 1926—a span of 36½ years.Chessmetrics also considers him the strongest 67-year-old in history: in December 1935, at age 67 years and 0 months, his rating was 2691 (number 7 in the world), well above second-place Viktor Korchnoi's rating at that age (2660, number 39 in the world, in March 1998).

Influence on chess

Lasker founded no school of players who played in a similar style.Max Euwe, World Champion 1935–1937 and a prolific writer of chess manuals, who had a lifetime 0–3 score against Lasker, said, "It is not possible to learn much from him. One can only stand and wonder." However, Lasker's pragmatic, combative approach had a great influence on Soviet players like Mikhail Tal and Viktor Korchnoi.

There are several "Lasker Variations" in the chess openings, including Lasker's Defense to the Queen's Gambit, Lasker's Defense to the Evans Gambit (which effectively ended the use of this gambit in tournament play until a revival in the 1990s), and the Lasker Variation in the McCutcheon Variation of the French Defense.

One of Lasker's most famous games is Lasker–Bauer, Amsterdam 1889, in which he sacrificed both bishops in a maneuver later repeated in a number of games. Similar sacrifices had already been played by Cecil Valentine De Vere and John Owen, but these were not in major events and Lasker probably had not seen them.

Lasker was shocked by the poverty in which Wilhelm Steinitz died and did not intend to die in similar circumstances. He became notorious for demanding high fees for playing matches and tournaments, and he argued that players should own the copyright in their games rather than let publishers get all the profits.These demands initially angered editors and other players, but helped to pave the way for the rise of full-time chess professionals who earn most of their living from playing, writing and teaching.Copyright in chess games had been contentious at least as far back as the mid-1840s, and Steinitz and Lasker vigorously asserted that players should own the copyright and wrote copyright clauses into their match contracts. However, Lasker's demands that challengers should raise large purses prevented or delayed some eagerly awaited World Championship matches—for example Frank James Marshall challenged him in 1904 to a match for the World Championship but could not raise the stakes demanded by Lasker until 1907. This problem continued throughout the reign of his successor, Capablanca.

Some of the controversial conditions that Lasker insisted on for championship matches led Capablanca to attempt twice (1914 and 1922) to publish rules for such matches, to which other top players readily agreed.

Work in other fields

Lasker was also a mathematician. In his 1905 article on commutative algebra, Lasker introduced the theory of primary decomposition of ideals, which has influence in the theory of Noetherian rings. Rings having the primary decomposition property are called "Laskerian rings" in his honor.

His attempt to create a general theory of all competitive activities were followed by more consistent efforts from von Neumann on game theory, and his later writings about card games presented a significant issue in the mathematical analysis of card games.

However, his dramatic and philosophical works have never been highly regarded.

St. Petersburg. 1896. Pillsbury - Lasker

Lasker, med svart, ofret begge tårnene på a3 ( ! ) først i trekk 18 og deretter i trekk 26 etter disse 26 trekkene :

1. d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c5 5.Bg5 cxd4 6.Qxd4Nc6 7.Qh4 Be7 8.O-O-O Qa5 9.e3 Bd7 10.Kb1 h6 11.cxd5 exd5 12.Nd4 O-O 13.Bxf6 Bxf6 14.Qh5 Nxd4 15.exd4 Be6 16.f4 Rac8 17.f5 Rxc3 18.fxe6 Ra3 19.exf7+Rxf7 20.bxa3 Qb6+ 21.Bb5 Qxb5+ 22.Ka1 Rc7 23.Rd2 Rc4 24.Rhd1 Rc3 25.Qf5 Qc4 26.Kb2 Rxa3

Stillingen på brettet var da slik:

Da Pillsbury tok det siste tårnet i trekk 26, satte Lasker Pillsbury forsert matt med følgende trekk:

27.Qe6+ Kh7 28. Kxa3 Qc3+ 29. Ka4 b5+ 30. Kxb5 Qc4+ med følgende stilling på brettet:

Etter Ka5 i neste trekk spilles løperen til d8 med matt : 31.Ka5 Bd8#.

3. JOSE RAUL CAPABLANCA

José Raúl Capablanca y Graupera (19 November 1888 – 8 March 1942) was a Cuban chess player who was world chess champion from 1921 to 1927. A chess prodigy, he is considered by many one of the greatest players of all time, widely renowned for his exceptional endgame skill and speed of play.

Born in Havana, he beat Cuban champion Juan Corzo in a match on 17 November 1901, two days before his 13th birthday.

His victory over Frank Marshall in a 1909 match earned him an invitation to the 1911 San Sebastian tournament, which

he won ahead of players such as Akiba Rubinstein, Aron Nimzowitsch and Siegbert Tarrasch. Over the next several years, Capablanca had a strong series of tournament results. After several unsuccessful attempts to arrange a match with then world champion Emanuel Lasker, Capablanca finally won the title from Lasker in 1921. Capablanca was undefeated from 10 February 1916 to 21 March 1924, a period that included the world championship match with Lasker.

Capablanca lost the title in 1927 to Alexander Alekhine, who had never beaten Capablanca before the match. Following

unsuccessful attempts to arrange a rematch over many years, relations between them became bitter. Capablanca continued his excellent tournament results in this period but withdrew from serious chess in 1931. He made a comeback in 1934, with some good results, but also showed symptoms of high blood pressure. His last major tournament was the AVRO tournament of 1938, where he performed disappointingly. He died in 1942 of a brain hemorrhage.

Capablanca excelled in simple positions and endgames; Bobby Fischer described him as possessing a "real light touch". He could play tactical chess when necessary, and had good defensive technique. He wrote several chess books during his career, of which Chess Fundamentals was regarded by Mikhail Botvinnik as the best chess book ever written. Capablanca preferred not to present detailed analysis but focused on critical moments in a game. His style of chess was influential in the play of future world champions Bobby Fischer and Anatoly Karpov.

Childhood

José Raúl Capablanca, the second surviving son of a Spanish army officer, was born in Havana on November 19, 1888. According to Capablanca, he learned to play chess at the age of four by watching his father play with friends, pointed out an illegal move by his father, and then beat his father. At the age of eight he was taken to Havana Chess Club, which had hosted many important contests, but on the advice of a doctor he was not allowed to play frequently. Between November and December 1901, he narrowly beat the Cuban Chess Champion, Juan Corzo, in a match. However, in April 1902 he came in fourth out of six in the National Championship, losing both his games with Corzo. In 1905 Capablanca easily passed the entrance examinations for Columbia University in New York City, where he wished to play for Columbia's strong baseball team, and soon was starting shortstop on the freshman team. In the same year he joined the Manhattan Chess Club, and was soon recognized as the club's strongest player. He was particularly dominant in rapid chess, winning a tournament ahead of the reigning World Chess Champion, Emanuel Lasker, in 1906. He represented Columbia on top board in intercollegiate team chess. In 1908 he left the university to concentrate on chess.

According to Columbia University, Capablanca enrolled at Columbia's School of Mines, Engineering and Chemistry in September, 1910, to study chemical engineering. Later, his financial support was withdrawn because he preferred playing chess to studying engineering. He left Columbia after one semester to devote himself to chess full-time.

Early adult career

Capablanca's skill in rapid chess lent itself to simultaneous exhibitions, and his increasing reputation in these events led to a US-wide tour in 1909. Playing 602 games in 27 cities, he scored 96.4%—a much higher percentage than, for example, Géza Maróczy's 88% and Frank Marshall's 86% in 1906. This performance gained him sponsorship for an exhibition match that year against Marshall, the US champion, who had won the 1904 Cambridge Springs tournament ahead of World Champion Emanuel Lasker and Dawid Janowski, and whom Chessmetrics ranks as one of the world's top three players at his peak. Capablanca beat Marshall, 15–8 (8 wins, 1 loss, 14 draws)—a margin comparable to what Lasker achieved against Marshall (8 wins, no losses, 7 draws) in winning his 1907 World Championship match. After the match, Capablanca said that he had never opened a book on chess openings. Following this match, Chessmetrics rates Capablanca the world's third strongest player for most of the period from 1909 through 1912.

Capablanca won six games and drew one in the 1910 New York State Championship. Both Capablanca and Charles Jaffe won their four games in the knock-out preliminaries and met in a match to decide the winner, who would be the first to win two games. The first game was drawn and Capablanca won the second and third games. After another grueling series of simultaneous exhibitions,[10] Capablanca placed second, with 9½ out of 12, in the 1911 National Tournament at New York, half a point behind Marshall, and half a point ahead of Charles Jaffe and Oscar Chajes. Marshall, invited to play in a tournament at San Sebastián, Spain, in 1911, insisted that Capablanca also be allowed to play.

According to David Hooper and Ken Whyld, San Sebastián 1911 was "one of the strongest five tournaments held up to that time", as all the world's leading players competed except the World Champion, Lasker. At the beginning of the tournament, Ossip Bernstein and Aron Nimzowitsch objected to Capablanca's participation because he had not fulfilled the entry condition of winning at least third prize in two master tournaments. Capablanca won brilliantly against Bernstein in the very first round, more simply against Nimzowitsch, and astounded the chess world by taking first place, with six wins, one loss and seven draws, ahead of Akiba Rubinstein, Milan Vidmar, Marshall, Carl Schlechter and Siegbert Tarrasch, et al. His loss, to Rubinstein, was one of the most brilliant achievements of the latter's career. Some European critics grumbled that Capablanca's style was rather cautious, though he conceded fewer draws than any of the next six finishers in the event. Capablanca was now recognized as a serious contender for the world championship.

World title contender

In 1911, Capablanca challenged Lasker for the World Chess Championship. Lasker accepted his challenge while proposing 17 conditions for the match. Capablanca objected to some of the conditions, which favored Lasker, and the match did not take place.

In 1913, Capablanca won a tournament in New York with 11/13, half a point ahead of Marshall. Capablanca then finished second to Marshall in Havana, scoring 10 out of 14 and losing one of their individual games. The 600 spectators naturally favored their native hero, but sportingly gave Marshall "thunderous applause". In a tournament in New York in 1913, at the Rice Chess Club, Capablanca won all 13 games.

Capablanca vs Alekhine. The St. Petersburg 1914 chess tournament.

In September 1913, Capablanca accepted a job in the Cuban Foreign Office, which made him financially secure for life. Hooper and Whyld write, "He had no specific duties, but was expected to act as a kind of ambassador-at-large, a well-known figure who would put Cuba on the map wherever he travelled." His first instructions were to go to Saint Petersburg, where he was due to play in a major tournament.[10] On his way, he gave simultaneous exhibitions in London, Paris and Berlin, where he also played two-game matches against Richard Teichmann and Jacques Mieses, winning all four games. In Saint Petersburg, he played similar matches against Alexander Alekhine, Eugene Znosko-Borovsky and Fyodor Duz-Chotimirsky, losing one game to Znosko-Borovsky and winning the rest.

The St. Petersburg 1914 chess tournament was the first in which Capablanca confronted Lasker under tournament conditions.[10] This event was arranged in an unusual way: after a preliminary single round-robin tournament involving 11 players, the top five were to play a second stage in double round-robin format, with total scores from the preliminary tournament carried forward to the second contest. Capablanca placed first in the preliminary tournament, 1½ points ahead of Lasker, who was out of practice and had made a shaky start. Despite a determined effort by Lasker, Capablanca still seemed on course for ultimate victory. But in their second game of the final, Lasker reduced Capablanca to a helpless position and Capablanca was so shaken by this that he blundered away his next game to Tarrasch. Lasker then won his final game, against Marshall, thus finishing half a point ahead of Capablanca and 3½ ahead of Alekhine. Alekhine commented:

His real, incomparable gifts first began to make themselves known at the time of St. Petersburg, 1914, when I too came to know him personally. Neither before nor afterwards have I seen—and I cannot imagine as well—such a flabbergasting quickness of chess comprehension as that possessed by the Capablanca of that epoch. Enough to say that he gave all the St. Petersburg masters the odds of 5–1 in quick games—and won! With all this he was always good-humoured, the darling of the ladies, and enjoyed wonderful good health—really a dazzling appearance. That he came second to Lasker must be entirely ascribed to his youthful levity—he was already playing as well as Lasker.

After the breakdown of his attempt to negotiate a title match in 1911, Capablanca drafted rules for the conduct of future challenges, which were agreed to by the other top players at the 1914 Saint Petersburg tournament, including Lasker, and approved at the Mannheim Congress later that year. The main points were: the champion must be prepared to defend his title once a year; the match should be won by the first player to win six or eight games, whichever the champion preferred; and the stake should be at least £1,000 (worth about £26,000 or $44,000 in 2013 terms.

During World War I

World War I began in midsummer 1914, bringing international chess to a virtual halt for more than four years.Capablanca won tournaments in New York in 1914, 1915, 1916 (with preliminary and final round-robin stages) and 1918, losing only one game in this sequence. In the 1918 event, Marshall, playing Black against Capablanca, unleashed a complicated counterattack, later known as the Marshall Attack, against the Ruy Lopez opening. It is often said that Marshall had kept this secret for use against Capablanca since his defeat in their 1909 match; however, Edward Winter discovered several games between 1910 and 1918 where Marshall passed up opportunities to use the Marshall Attack against Capablanca; and an 1893 game that used a similar line. This gambit is so complex that Garry Kasparov used to avoid it, and Marshall had the advantage of using a prepared variation. Nevertheless, Capablanca found a way through the complications and won. Capablanca was challenged to a match in 1919 by Borislav Kostić, who had come through the 1918 tournament undefeated to take second place. The match was to go to the first player to win eight games, but Kostić resigned the match after losing the first five. Capablanca considered that he was at his strongest around this time.

World Champion

The Hastings Victory tournament of 1919 was the first international competition on Allied soil since 1914. The field was not strong, and Capablanca won with 10½ points out of 11, one point ahead of Kostić.

In January 1920, Lasker and Capablanca signed an agreement to play a World Championship match in 1921, noting that Capablanca was not free to play in 1920. Because of the delay, Lasker insisted that if he resigned the title, then Capablanca should become World Champion. Lasker had previously included in his agreement before World War I to play Akiba Rubinstein for the title a similar clause that if he resigned the title, it should become Rubinstein's. Lasker then resigned the title to Capablanca on June 27, 1920, saying, "You have earned the title not by the formality of a challenge, but by your brilliant mastery." When Cuban enthusiasts raised $20,000 to fund the match provided it was played in Havana, Lasker agreed in August 1920 to play there, but insisted that he was the challenger as Capablanca was now the champion. Capablanca signed an agreement that accepted this point, and soon afterwards published a letter confirming it.

The match was played in March–April 1921; Lasker resigned it after 14 games, having lost four and won none. Reuben Fine and Harry Golombek attributed the one-sided result to Lasker's mysteriously poor form. Fred Reinfeld mentioned speculations that Havana's humid climate weakened Lasker and that he was depressed about the outcome of World War I, especially as he had lost his life savings. On the other hand, Vladimir Kramnik thought that Lasker played quite well and the match was an "even and fascinating fight" until Lasker blundered in the last game. Kramnik explained that Capablanca was 20 years younger, a slightly stronger player, and had more recent competitive practice.

Edward Winter, after a lengthy summary of the facts, concludes, "The press was dismissive of Lasker's wish to confer the title on Capablanca, even questioning the legality of such an initiative, and in 1921 it regarded the Cuban as having become world champion by dint of defeating Lasker over the board."[36] Reference works invariably give Capablanca's reign as titleholder as beginning in 1921, not 1920. The two challengers beside Capablanca to win the title without losing a game are Kramnik, in the Classical World Chess Championship 2000 against Garry Kasparov, and Magnus Carlsen in the World Chess Championship 2013 against Viswanathan Anand.

Capablanca won the London tournament of 1922 with 13 points in 15 games with no losses, ahead of Alekhine with 11½, Milan Vidmar (11), and Akiba Rubinstein (10½). During this event, Capablanca proposed the "London Rules" to regulate future World Championship negotiations: the first player to win six games would win the match; playing sessions would be limited to 5 hours; the time limit would be 40 moves in 2½ hours; the champion must defend his title within one year of receiving a challenge from a recognized master; the champion would decide the date of the match; the champion was not obliged to accept a challenge for a purse of less than US$10,000 (about $260,000 in 2006 terms); 20% of the purse was to be paid to the title holder and the remainder divided, 60% to the winner of the match, and 40% to the loser; the highest purse bid must be accepted. Alekhine, Efim Bogoljubow, Géza Maróczy, Richard Réti, Rubinstein, Tartakower and Vidmar promptly signed them. Between 1921 and 1923 Alekhine, Rubinstein and Nimzowitsch all challenged Capablanca, but only Alekhine could raise the money, in 1927.

In 1922, Capablanca also gave a simultaneous exhibition in Cleveland against 103 opponents, the largest in history up to that time, winning 102 and drawing one—setting a record for the best winning percentage ever in a large simultaneous exhibition.