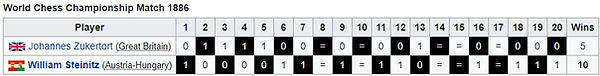

The full World Championship match results:

Get rythm (Joaquin Phoenix / Johnny Cash)

Hey get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

Get a rock and roll feelin' in your bones

Get taps on your toes and get gone

Get rhythm when you get the blues

A little shoeshine boy he never gets lowdown

But he's got the dirtiest job in town

Bendin' low at the people's feet

On a windy corner of a dirty street

Well I asked him while he shined my shoes

How'd he keep from gettin' the blues

He grinned as he raised his little head

He popped his shoeshine rag and then he said

Get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

Yes a jumpy rhythm makes you feel so fine

It'll shake all your troubles from your worried mind

Get rhythm when you get the blues

Get rhythm when you get the blues

Get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

Get a rock and roll feelin' in your bones

Get taps on your toes and get gone

Get rhythm when you get the blues

Well I sat and listened to the sunshine boy

I thought I was gonna jump with joy

He slapped on the shoe polish left and right

He took his shoeshine rag and he held it tight

He stopped once to wipe the sweat away

I said you mighty little boy to be a workin' that way

He said I like it with a big wide grin

Kept on a poppin' and he'd say it again

Get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

It only cost a dime just a nickel a shoe

It does a million dollars worth of good for you

Get rhythm when you get the blues

For the good times (Kris Kristofferson)

Don't look so sad. I know it's over

But life goes on and this world keeps on turning

Let's just be glad we had this time to spend together

There is no need to watch the bridges that we're burning

Lay your head upon my pillow

Hold your warm and tender body close to mine

Hear the whisper of the raindrops

Blow softly against my window

Make believe you love me one more time

For the good times

I'll get along; you'll find another,

And I'll be here if you should find you ever need me.

Don't say a word about tomorrow or forever,

There'll be time enough for sadness when you leave me.

Lay your head upon my pillow

Hold your warm and tender body Close to mine

Hear the whisper of the raindrops

Blow softly against my window

Make believe you love me

One more time

For the good times

STABELVOLLEN MEDIA

Copyright of all music videoes, guest photoes and artworks solely belongs to the artists. Copyright of all other resources : Stabelvollen Media.

CHESS WORLD CHAMPIONS 1969 - 1975

Boris Vasilievich Spassky (Russian: Бори́с Васи́льевич Спа́сский; born January 30, 1937) is a Russian chess grandmaster. He was the tenth World Chess Champion, holding the title from 1969 to 1972. Spassky played three world championship matches: he lost to Tigran Petrosian in 1966; defeated Petrosian in 1969 to become world champion; then lost to Bobby Fischer in a famous match in 1972.

Spassky won the Soviet Chess Championship twice outright (1961, 1973), and twice lost in playoffs (1956, 1963), after tying for first place during the event proper. He was a World Chess Championship candidate on seven occasions (1956, 1965, 1968, 1974, 1977, 1980, and 1985). In addition to his candidates wins in 1965 and 1968, he reached the semi-final stage in 1974 and the final stage in 1977.

Spassky emigrated to France in 1976, becoming a French citizen in 1978. He continued to compete in tournaments but was no longer a major contender for the world title. He lost an unofficial rematch against Fischer in 1992. In 2012 he left France and returned to Russia. He is the oldest living former world champion.

10. BORIS SPASSKY

Early life

Spassky was born in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) to Russian parents. His father Vasili Vladimirovich Spassky served in the military. He came from the family of Vladimir Alexandrovich Spassky, a prominent Russian Orthodox priest of the Kursk Governorate, later a protoiereus of the Russian Church (since 1916), as well as a State Duma deputy (1912–1917) and an active member of the Union of the Russian People. Boris' mother Ekaterina Petrovna Spasskaya (nee Petrova) was a school teacher. She was born in the Ryadnevo village of the Gdov district (now Pskov Oblast) as an illegitimate daughter of Daria Ivanovna Ivanova (who belonged to local peasants) and Andrei Kupriyanovich Kupriyanov, a landlord who owned houses in Saint Petersburg and Pskov. After some time Daria Ivanovna fled to Petersburg, leaving her daughter with Petr Vasiliev, a relative of hers, who raised Ekaterina under the surname of Petrova. She joined her mother later on.

Spassky learned to play chess at the age of 5 on a train evacuating from Leningrad during the siege of Leningrad in World War II. He first drew wide attention in 1947 at age 10, when he defeated Soviet champion Mikhail Botvinnik in a simultaneous exhibition in Leningrad. Spassky's early coach was Vladimir Zak, a respected master and trainer. During his youth, from the age of 10, Spassky often worked on chess for several hours a day with master-level coaches. He set records as the youngest Soviet player to achieve first category rank (age 10), candidate master rank (age 11), and Soviet Master rank (age 15). In 1952, at 15, Spassky scored 50 percent in the Soviet Championship semi-final at Riga, and placed second in the Leningrad Championship that same year, being highly praised by Botvinnik.

Career

As a statistic encompassing all of the games of his career, Spassky's most-played openings with both the White and Black pieces were the Sicilian Defence and the Ruy Lopez.

Spassky has beaten six undisputed World Champions at least twice (not necessarily while they were reigning): Vasily Smyslov, Mikhail Tal, Tigran Petrosian, Bobby Fischer, Anatoly Karpov, and Garry Kasparov.

Young grandmaster

Spassky made his international debut in 1953, aged 16, in Bucharest, Romania, finishing tied for fourth place[9] with Laszlo Szabo on 12/19, an event won by his trainer, Alexander Tolush. At Bucharest he defeated Vasily Smyslov, who challenged for the World Championship the following year. He was awarded the title of International Master by FIDE. In his first attempt at the Soviet Championship final, the 22nd in the series, held in Moscow 1955, Spassky tied for third place with 11½/19, after Smyslov and Efim Geller, which was sufficient to qualify him for the Gothenburg Interzonal later that year.

The same year, he won the World Junior Chess Championship held at Antwerp, Belgium, scoring 6/7 to qualify for the final, then 8/9 in the final to win by a full point over Edmar Mednis. Spassky competed for the Lokomotiv Voluntary Sports Society.

By sharing seventh place with 11/20 at Gothenburg, Spassky qualified for the 1956 Candidates' Tournament, held in Amsterdam, automatically gaining the grandmaster title, and was then the youngest to hold the title. At Amsterdam, he tied for third place with four others in the ten-player field, scoring 9½/18. At the 23rd Soviet final, held in Leningrad in January–February 1956, Spassky shared first place on 11½/19, with Mark Taimanov and Yuri Averbakh, but Taimanov won the subsequent playoff to become champion, defeating Spassky in both their games. Spassky then tied for first in a semifinal for the 24th Soviet championship, thereby qualifying.

Uneven results

Spassky then went into a slump in world championship qualifying events, failing to advance to the next two Interzonals (1958 and 1962), a prerequisite to earn the right to play for the world championship. This crisis coincided with the hard three final years of his first marriage before his divorce in 1961, the same year that he broke with his trainer Tolush.

In the 24th Soviet final, played at Moscow in January–February 1957, Spassky shared fourth place with Tolush, as both scored 13/21, while Mikhail Tal won the first of his six Soviet titles, which began his ascent to the world title in 1960.

Spassky's failure to qualify for the Portoroz Interzonal came after a last-round defeat at the hands of Tal, in a nervy game in the 1958 Soviet championship, held at Riga. Spassky had the advantage for much of the game, but missed a difficult win after adjournment, then declined a draw. A win would have qualified Spassky for the Interzonal, and a draw would have ensured a share of fourth place with Yuri Averbakh, with qualification possible via a playoff.

Spassky tied for first place at Moscow 1959 on 7/11, with Smyslov and David Bronstein. He shared second place in the 26th Soviet final with Tal, at Tbilisi 1959, finishing a point behind champion Tigran Petrosian, on 12½/19. Soon after Spassky notched a victory at Riga 1959, with 11½/13, one-half point in front of Vladas Mikėnas. Spassky finished in a tie for ninth at the 27th Soviet final in Leningrad, with 10/19, as fellow Leningrader Viktor Korchnoi scored his first of four Soviet titles. Spassky travelled to Argentina, where he shared first place with Bobby Fischer, two points ahead of Bronstein, at Mar del Plata 1960 on 13½/15, defeating Fischer in their first career meeting. Spassky played on board one for the USSR at the 7th Student Olympiad in Leningrad, where he won the silver, but lost the gold to William Lombardy, also losing their individual encounter.

Another disappointment for Spassky came at the qualifier for the next Interzonal, the Soviet final, played in Moscow 1961, where he again lost a crucial last-round

game, this to Leonid Stein, who thus qualified, as Spassky finished equal fifth with 11/19, while Petrosian won.

Title contender

Spassky decided upon a switch in trainers, from the volatile attacker Alexander Tolush to the calmer strategist Igor Bondarevsky. This proved the key to his resurgence. He won his first of two USSR titles in the 29th Soviet championship at Baku 1961, with a score of 14½/20, one-half point ahead of Lev Polugaevsky.[30] Spassky shared second with Polugaevsky at Havana 1962 with 16/21, behind winner Miguel Najdorf.[31] He placed joint fifth, with Leonid Stein at the 30th Soviet championship held in Yerevan 1962, with 11½/19. At Leningrad 1963, the site of the 31st Soviet final, Spassky tied for first with Stein and Ratmir Kholmov, with Stein winning the playoff, which was held in 1964. Spassky won at Belgrade 1964 with an undefeated 13/17, as Korchnoi and Borislav Ivkov shared second place with 11½. He finished fourth at Sochi 1964 with 9½/15, as Nikolai Krogius won.

In the 1964 Soviet Zonal at Moscow, a seven-player double round-robin event, Spassky won with 7/12, overcoming a start of one draw and two losses, to advance to the Amsterdam Interzonal the same year. At Amsterdam, he tied for first place, along with Mikhail Tal, Vasily Smyslov and Bent Larsen on 17/23, with all four, along with Borislav Ivkov and Lajos Portisch thus qualifying for the newly created Candidates' Matches the next year. With Bondarevsky, Spassky's style broadened and deepened, with poor results mostly banished, yet his fighting spirit was even enhanced. He added psychology and surprise to his quiver, and this proved enough to eventually propel him to the top.

Challenger

Spassky was considered an all-rounder on the chess board, and his adaptable "universal style" was a distinct advantage in beating many top grandmasters. In the 1965 cycle, he beat Paul Keres in the quarterfinal round at Riga 1965 with careful strategy, triumphing in the last game to win 6–4 (+4−2=4). Also at Riga, he defeated Efim Geller with mating attacks, winning by 5½–2½ (+3−0=5). Then, in his Candidates' Final match against Mikhail Tal at Tbilisi 1965, Spassky often managed to steer play into quieter positions, either avoiding former champion Tal's tactical strength, or exacting too high a price for complications. Though losing the first game, he won by 7–4 (+4−1=6).

Spassky won two tournaments in the run-up to the final. He shared first at the third Chigorin Memorial in Sochi, in 1965 with Wolfgang Unzicker on 10½/15, then tied for first at Hastings 1965–66 with Wolfgang Uhlmann on 7½/9.

Spassky lost a keenly fought match to Petrosian in Moscow, with three wins against Petrosian's four, with seventeen draws, though the last of his three victories came only in the twenty-third game, after Petrosian had ensured his retention of the title, the first outright match victory for a reigning champion since the latter of Alekhine's successful defences against Bogoljubov in 1934. Spassky's first event after the title match was the fourth Chigorin Memorial, where he finished tied for fifth with Anatoly Lein as Korchnoi won. Spassky then finished ahead of Petrosian and a super-class field at Santa Monica 1966 (the Piatigorsky Cup), with 11½/18, half a point ahead of Bobby Fischer, as he overcame the American grandmaster's challenge after Fischer had scored 3½/9 in the first cycle of the event. Spassky also won at Beverwijk 1967 with 11/15, one-half point ahead of Anatoly Lutikov, and shared first place at Sochi 1967 on 10/15 with Krogius, Alexander Zaitsev, Leonid Shamkovich, and Vladimir Simagin.

As losing finalist in 1966, Spassky was automatically seeded into the next Candidates' cycle. In 1968, he faced Geller again, this time at Sukhumi, and won by the same margin as in 1965 (5½–2½, +3−0=5). He next met Bent Larsen at Malmö, and again won by the score of 5½–2½ after winning the first three games. The final was against his Leningrad rival Korchnoi at Kiev, and Spassky triumphed (+4−1=5), which earned him another match with Petrosian. Spassky's final tournament appearance before the match came at Palma, where he shared second place (+10−1=6) with Larsen, a point behind Korchnoi. Spassky's flexibility of style was the key to victory over Petrosian, by 12½–10½, with the site again being Moscow.

World Champion

In Spassky's first appearance after winning the crown, he placed first at San Juan in October 1969 with 11½/15, one and one-half points clear of second. He then played the annual event at Palma, where he finished fifth with 10/17. While Spassky was undefeated and handed tournament victor Larsen one of his three losses, his fourteen draws kept him from seriously contending for first prize, as he came two points behind Larsen. In March–April 1970, Spassky played first board for the Soviet side in the celebrated USSR vs World event at Belgrade, where he scored +1−1=1 in the first three rounds against Larsen before Stein replaced him for the final match, as the Soviets won by the odd point, 20½–19½. He won a quadrangular event at Leiden 1970 with 7/12, a point ahead of Jan Hein Donner, who was followed by Larsen and Botvinnik, the latter of whom was making his final appearance in serious play. Spassky shared first at the annual IBM event held in Amsterdam 1970 with Polugaevsky on 11½/15. He was third at Gothenburg 1971 with 8/11, behind winners Vlastimil Hort and Ulf Andersson. He shared first with Hans Ree at the 1971 Canadian Open in Vancouver. In November and December, Spassky finished the year by tying for sixth with Tal, scoring +4−2=11, at the Alekhine Memorial in Moscow, which was won by Stein and Anatoly Karpov, the latter's first top-class success.

Championship match with Fischer

Spassky's reign as world champion lasted for three years, as he lost to Fischer of the United States in 1972 in the World Chess Championship 1972, popularly known as the Match of the Century. The contest took place in Reykjavík, Iceland, at the height of the Cold War, and consequently was seen as symbolic of the political confrontation between the two superpowers. Spassky accommodated many demands by Fischer, including moving the third game into a side room. The Fischer vs Spassky World championship was the most widely covered chess match in history, as mainstream media throughout the world covered the match. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger spoke with Fischer urging him to play the match, and chess was at its apex.

Going into the match, Fischer had never won a game from Spassky in five attempts, losing three. In addition, Spassky had secured Geller as his coach, who also had a plus score against Fischer. However, Fischer won the title match 121⁄2/81⁄2 (+7−3=11), with one of the three losses by default.

The match could be divided into halves, the first won convincingly by Fischer, and the second a close battle. Before Spassky, Mark Taimanov, Bent Larsen, and Tigran Petrosian, had lost to Fischer, but Spassky maintained his composure and competitiveness. It has been suggested that Spassky's preparation was largely bypassed by Fischer, since Spassky and his team wrongly expected Fischer to always play 1. e4 openings as White.

Ex-champion (1973–1985)

In February–March 1973, Spassky finished equal third at Tallinn with 9/15, three points behind Tal; he tied for first at Dortmund on 9½/15 (+5−1=9) with Hans-Joachim Hecht and Ulf Andersson. Spassky finished in fourth place at the annual IBM tournament held in Amsterdam, one point behind winners Petrosian and Albin Planinc. In September, Spassky went 10/15 to finish second to Tal in the Chigorin Memorial at Sochi by a point. In the 41st Soviet Championship at Moscow, Spassky scored 11½/17 to win by a full point in a field which included all the top Soviet grandmasters of the time.

In the 1974 Candidates' matches, Spassky first defeated American Robert Byrne in San Juan, Puerto Rico by 4½–1½ (+3−0=3); he then lost the semifinal match to Anatoly Karpov in Leningrad, despite winning the first game, (+1−4=6). In Spassky's only tournament action of 1974, he played at Solingen, finishing with 8½/14 (+4−1=9), thus sharing third with Bojan Kurajica, behind joint winners Lubomir Kavalek and Polugaevsky, who scored 10.

During 1975, Spassky played two events, the first being the annual tournament at Tallinn, where he finished equal second with Fridrik Olafsson, scoring 9½/15 (+5−1=9), one point behind Keres, the last international event won by the latter before his sudden death in June 1975. In October–November, Spassky finished second to Geller at the Alekhine Memorial in Moscow with a score of 10 points from fifteen games (+6−1=8).

In 1976, Spassky was obliged to return to the Interzonal stage, and finished in a tie for tenth place in Manila, well short of qualifying for the Candidates matches, but was nominated to play after Fischer declined his place. Spassky won an exhibition match with Dutch grandmaster Jan Timman at Amsterdam 1977 by 4–2. He triumphed in extra games in his quarterfinal Candidates' match over Vlastimil Hort at Reykjavík 1977 by 8½–7½. This match saw Spassky fall ill, exhaust all his available rest days while recovering;[citation needed] then the healthy Hort used one of his own rest days, to allow Spassky more time to recover; Spassky eventually won the match.

Spassky won an exhibition match over Robert Hübner at Solingen, 1977 by 3½–2½, then defeated Lubomir Kavalek, also at Solingen, by 4–2 in another exhibition. His next Candidates' match was against Portisch at Geneva 1977, and Spassky won by 8½–6½, to qualify for the final. At Belgrade 1977–78, Spassky lost to Korchnoi, by (+4−7=7). In this match, Spassky fell behind 2½–7½ after losing the tenth game; however, he then won four consecutive games. After draws in games fifteen and sixteen, Korchnoi won the next two games to clinch the match by the score of 10½–7½.

Spassky, as losing finalist, was seeded into the 1980 Candidates' matches, and faced Portisch again, with this match held in Mexico. After fourteen games, the match was 7–7, but Portisch advanced since he had won more games with the black pieces.[84] Spassky missed qualification from the 1982 Toluca Interzonal with 8/13, finishing half a point short, in third place behind Portisch and Eugenio Torre,[85] both of whom thus qualified. The 1985 Candidates' event was held as a round-robin tournament at Montpellier, France, and Spassky was nominated as an organizer's choice. He scored 8/15 to tie for sixth place with Alexander Beliavsky, behind joint winners Andrei Sokolov, Rafael Vaganian, and Artur Yusupov, and one-half point short of potentially qualifying via a playoff. This was Spassky's last appearance at the Candidates' level.

Later tournament career (after 1976)

In his later years, Spassky showed a reluctance to devote himself completely to chess. In 1976, Spassky emigrated to France with his third wife; he became a French citizen in 1978, and has competed for France in the Chess Olympiads. Spassky later lived with his wife in Meudon near Paris.

Spassky did, however, score some notable triumphs in his later years. In his return to tournament play after the loss to Korchnoi, he tied for first at Bugojno 1978 on 10/15 with Karpov, with both players scoring +6-1=8 to finish a point ahead of Timman. He was clear first at Montilla–Moriles 1978 with 6½/9.At Munich 1979, he tied for first place with 8½/13,[95] with Yuri Balashov, Andersson and Robert Hübner. He shared first at Baden in 1980, on 10½/15 with Alexander Beliavsky. He won his preliminary group at Hamburg 1982 with 5½/6, but lost the final playoff match to Anatoly Karpov in extra games. His best result during this period was clear first at Linares 1983 with 6½/10, ahead of Karpov and Ulf Andersson, who shared second. At London Lloyds' Bank Open 1984, he tied for first with John Nunn and Murray Chandler, on 7/9. He won at Reykjavík 1985. At Brussels 1985, he placed second with 10½/13 behind Korchnoi. At Reggio Emilia 1986, he tied for 2nd–5th places with 6/11 behind Zoltán Ribli. He swept Fernand Gobet 4–0 in a match at Fribourg 1987. He finished equal first at the Plaza tournament in the New Zealand International Festival of the Arts at Wellington in 1988, with Chandler and Eduard Gufeld. Spassky's Elo rating was in the world top ten continually throughout the early 1980s until it dropped out in 1983, and intermittently throughout the mid 1980s until it dropped out for the final time in 1987.

However, Spassky's performances in the World Cup events of 1988 and 1989 showed that he could by this stage finish no higher than the middle of the pack against elite fields. He participated in three of the six events of the World Cup. At Belfort, he scored 8/15 for a joint 4th–7th place, as Garry Kasparov won. At Reykjavík, he scored 7/17 for a joint 15th–16th place, with Kasparov again winning. Finally, at Barcelona, Spassky scored 7½/16 for a tied 8th–12th place, as Kasparov shared first with Ljubomir Ljubojević.

Spassky played in the 1990 French Championship at Angers, placing fourth with 10½/15, as Marc Santo Roman won. At Salamanca 1991, he placed 2nd with 7½/11 behind winner Evgeny Vladimirov. Then in the 1991 French Championship at Montpellier, he scored 9½/15 for a tied 4th–5th place, as Santo Roman won again.

In 1992, Bobby Fischer, after a twenty-year hiatus from chess, re-emerged to arrange a "Revenge Match of the 20th century" against Spassky in Montenegro and Belgrade; this was a rematch of the 1972 World Championship. At the time, Spassky was rated 106th in the FIDE rankings, and Fischer did not appear on the list at all, owing to his inactivity. This match was essentially Spassky's last major challenge. Spassky lost the match with a score of +5−10=15. However, Spassky earned $1.65 million for losing the match. Spassky then played the young prodigy Judit Polgár in a 1993 match at Budapest, losing narrowly by 4½–5½.

Spassky continued to play occasional events through much of the 1990s, such as the Veterans vs Women match in Prague, 1995.

Life since 2000

On October 1, 2006, Spassky suffered a minor stroke during a chess lecture in San Francisco. In his first major post-stroke play, he drew a six-game rapid match with Hungarian Grandmaster Lajos Portisch in April 2007.

On 27 March 2010, at 73 years old, he became the oldest surviving former World Chess Champion following the death of Vasily Smyslov.

On September 23, 2010, ChessBase reported that Spassky had suffered a more serious stroke that had left him paralyzed on his left side. After that he returned to France for a long rehabilitation programme. On August 16, 2012, Spassky left France to return to Russia under disputed circumstances and now lives in an apartment in Moscow.

On 25 September 2016, he made a public speech at the opening of the Tal Memorial tournament. He said he had "the very brightest memories" of Mikhail Tal and told an anecdote from the 15th Chess Olympiad about Soviet analysis of an adjourned game between Fischer and Botvinnik. He was described by Chess24 as being 'sprightly'.

Legacy

Spassky's best years were as a youthful prodigy in the mid-1950s, and in the mid- to late 1960s. It is generally believed that he began to lose ambition once he became world champion. Some[who?] suggest the first match with Fischer took a severe nervous toll, but others disagree, and claim that as he was a sportsman who appreciated his opponent's skill. He applauded Fischer in Game 6 of their 1972 match, and defended Fischer when the latter was detained near Narita Airport in 2004.

Spassky has been described by many as a universal player. Never a true openings expert, at least when compared to contemporaries such as Geller and Fischer, he excelled in the middlegame and in tactics.

Spassky succeeded with a wide variety of openings, including the King's Gambit, 1.e4 e5 2.f4, an aggressive and risky line rarely seen at the top level. The chess game between "Kronsteen" and "McAdams" in the early part of the James Bond movie From Russia With Love is based on a game in that opening played between Spassky and David Bronstein in 1960 in which Spassky ("Kronsteen") was victorious.

His contributions to opening theory extend to reviving the Marshall Attack for Black in the Ruy Lopez (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Nf6 5.0-0 Be7 6.Re1 b5 7.Bb3 0-0 8.c3 d5), developing the Leningrad Variation for White in the Nimzo-Indian Defence (1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.Bg5), the Spassky Variation on the Black side of the Nimzo-Indian, and the Closed Variation of the Sicilian Defence for White (1.e4 c5 2.Nc3). A variation of the B19 Caro-Kann (1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.Nxe4 Bf5 5.Ng3 Bg6 6.h4 h6 7.Nf3 Nd7 8.h5) also bears his name, as does a rare line in the King's Indian Attack (1.Nf3 Nf6 2.g3 b5!?).

Spassky was played by Liev Schreiber in the 2014 film Pawn Sacrifice.

Boris Spassky vs Robert James Fischer. "Crime and Punishment" (game of the day Feb-03-2017)

Spassky - Fischer World Championship Match (1972), Reykjavik ISL, rd 11, Aug-06

Sicilian Defense: Najdorf. Poisoned Pawn Variation (B97) · 1-0

11. ROBERT JAMES FISCHER

Robert James Fischer (March 9, 1943 – January 17, 2008) was an American chess grandmaster and the eleventh World Chess Champion. Many consider him to be the greatest chess player of all time.

He showed great skill in chess from an early age; at 13, he won a brilliancy known as "The Game of the Century". At age 14, he became the US Chess Champion, and at 15, he became both the youngest grandmaster (GM) up to that time and the youngest candidate for the World Championship. At age 20, Fischer won the 1963/64 US Championship with 11 wins in 11 games, the only perfect score in the history of the tournament. His book My 60 Memorable Games, published in 1969, is regarded as essential reading. He won the 1970 Interzonal Tournament by a record 3½-point margin, and won 20 consecutive games, including two unprecedented 6–0 sweeps, in the Candidates Matches. In July 1971, he became the first official FIDE number-one-rated player.

Fischer won the World Chess Championship in 1972, defeating Boris Spassky of the USSR, in a match held in Reykjavík, Iceland. Publicized as a Cold War confrontation between the US and USSR, it attracted more worldwide interest than any chess championship before or since. In 1975, Fischer refused to defend his title when an agreement could not be reached with FIDE, chess's international governing body, over one of the conditions for the match. Under FIDE rules, this resulted in Soviet GM Anatoly Karpov, who had won the qualifying Candidates' cycle, being named the new world champion by default.

After forfeiting his title as World Champion, Fischer became reclusive and sometimes erratic, disappearing from both competitive chess and the public eye. In 1992, he reemerged to win an unofficial rematch against Spassky. It was held in Yugoslavia, which was under a United Nations embargo at the time. His participation led to a conflict with the US government, which warned Fischer that his participation in the match would violate an executive order imposing US sanctions on Yugoslavia. The US government ultimately issued a warrant for his arrest. After that, Fischer lived his life as an émigré. In 2004, he was arrested in Japan and held for several months for using a passport that had been revoked by the US government. Eventually, he was granted an Icelandic passport and citizenship by a special act of the Icelandic Althing, allowing him to live in Iceland until his death in 2008.

Fischer made numerous lasting contributions to chess. In the 1990s, he patented a modified chess timing system that added a time increment after each move, now a standard practice in top tournament and match play. He also invented Fischer random chess, a new variant of chess also known as Chess960.

Early years

Bobby Fischer was born at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago, Illinois, on March 9, 1943. His birth certificate listed his father as Hans-Gerhardt Fischer, also known as Gerardo Liebscher, a German biophysicist. His mother, Regina Wender Fischer, was a US citizen, born in Switzerland; her parents were Polish Jews Raised in St. Louis, Missouri,[5] Regina became a teacher, registered nurse, and later a physician.

After graduating from college in her teens, Regina traveled to Germany to visit her brother. It was there she met geneticist and future Nobel Prize winner Hermann Joseph Muller, who persuaded her to move to Moscow to study medicine. She enrolled at I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, where she met Hans-Gerhardt, whom she married in November 1933. In 1938, Hans-Gerhardt and Regina had a daughter, Joan Fischer. The reemergence of anti-Semitism under Stalin prompted Regina to go with Joan to Paris, where Regina became an English teacher. The threat of a German invasion led her and Joan to go to the United States in 1939. Regina and Hans-Gerhardt had separated in Moscow, although they did not officially divorce until 1945.

At the time of her son's birth, Regina was homeless and shuttled to different jobs and schools around the country to support her family. She engaged in political activism, and raised both Bobby and Joan as a single parent.

In 1949, the family moved to Manhattan and the following year to Brooklyn, New York City, where she studied for her master's degree in nursing and subsequently began working in that field.

Paul Nemenyi as Fischer's father

In 2002, Peter Nicholas and Clea Benson of The Philadelphia Inquirer published an investigative report backed by detailed and compelling evidence that indicated that Bobby Fischer's biological father was actually Paul Nemenyi. Nemenyi, a Hungarian mathematician and physicist of Jewish heritage, was considered an expert in fluid and applied mechanics. Benson and Nicholas continued their work and gathered additional evidence in court records, personal interviews, and even a summary of the FBI investigation written by J. Edgar Hoover, which supported their earlier conclusions.

Throughout the 1950s, the FBI investigated Regina and her circle for her alleged communist sympathies, as well as her time living in Moscow. FBI files note that Hans-Gerhardt Fischer never entered the United States, while recording that Nemenyi took a keen interest in Fischer's upbringing. Not only were Regina and Nemenyi reported to have had an affair in 1942, but Nemenyi made monthly child support payments to Regina and paid for Bobby's schooling until his own death in 1952. In addition, Nicholas and Benson found letters by Nemenyi's first son, Peter, identifying Bobby Fischer as his brother.

Chess beginnings

In March 1949, 6-year-old Bobby and his sister Joan learned how to play chess using the instructions from a set bought at a candy store. When Joan lost interest in chess and Regina did not have time to play, Fischer was left to play many of his first games against himself. When the family vacationed at Patchogue, Long Island, New York, that summer, Bobby found a book of old chess games and studied it intensely.

In 1950, the family moved to Brooklyn, first to an apartment at the corner of Union Street and Franklin Avenue, and later to a two-bedroom apartment at 560 Lincoln Place. It was there that "Fischer soon became so engrossed in the game that Regina feared he was spending too much time alone". As a result, on November 14, 1950, Regina sent a postcard to the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper, seeking to place an ad inquiring whether other children of Bobby's age might be interested in playing chess with him. The paper rejected her ad, because no one could figure out how to classify it, but forwarded her inquiry to Hermann Helms, the "Dean of American Chess", who told her that Master Max Pavey, former Scottish champion, would be giving a simultaneous exhibition on January 17, 1951.[29][30] Fischer played in the exhibition. Although he held on for 15 minutes, drawing a crowd of onlookers, he eventually lost to the chess master.

One of the spectators was Brooklyn Chess Club President, Carmine Nigro, an American chess expert of near master strength and an instructor. Nigro was so impressed with Fischer's play that he introduced him to the club and began teaching him. Fischer noted of his time with Nigro:"Mr. Nigro was possibly not the best player in the world, but he was a very good teacher. Meeting him was probably a decisive factor in my going ahead with chess."

William Lombardy and Fischer analyzing, with Jack Collins looking on

Nigro hosted Fischer's first chess tournament at his home in 1952. In the summer of 1955, Fischer, then 12 years old, joined the Manhattan Chess Club. Fischer's relationship with Nigro lasted until 1956, when Nigro moved away.

The Hawthorne Chess Club

In June 1956, Fischer began attending the Hawthorne Chess Club, based in master John "Jack" W. Collins' home. Collins taught chess to children, and has been described as Fischer's teacher, but Collins himself suggested that he did not actually teach Fischer, and the relationship might be more accurately described as one of mentorship.

Fischer played thousands of blitz and offhand games with Collins and other strong players, studied the books in Collins' large chess library, and ate almost as many dinners at Collins' home as his own.

Young champion

On the tenth national rating list of the United States Chess Federation (USCF), published on May 20, 1956, Fischer's rating was 1726, more than 900 points below top-rated Samuel Reshevsky (2663). His playing strength increased rapidly that year.

In March 1956, the Log Cabin Chess Club of West Orange, New Jersey (based in the home of the club's eccentric multi-millionaire founder and patron Elliot Forry Laucks) took Fischer on a tour to Cuba, where he gave a 12-board simultaneous exhibition at Havana's Capablanca Chess Club, winning ten games and drawing two. On this tour the club played a series of matches against other clubs. Fischer played second board, behind International Master Norman Whitaker. Whitaker and Fischer were the leading scorers for the club, each scoring 5½ points out of 7 games.

In July 1956, Fischer won the US Junior Chess Championship, scoring 8½/10 at Philadelphia to become the youngest-ever Junior Champion at age 13. At the 1956 US Open Chess Championship in Oklahoma City, he scored 8½/12 to tie for 4th–8th places, with Arthur Bisguier winning.In the first Canadian Open Chess Championship at Montreal 1956, he scored 7/10 to tie for 8th–12th places, with Larry Evans winning. In November, Fischer played in the 1956 Eastern States Open Championship in Washington, D.C., tying for second with William Lombardy, Nicholas Rossolimo, and Arthur Feuerstein, with Hans Berliner taking first by a half-point.

Fischer accepted an invitation to play in the Third Lessing J. Rosenwald Trophy Tournament in New York City (1956), a premier tournament limited to the 12 players considered the best in the country. Although Fischer's rating was not among the top 12 in the country, he received entry by special consideration. Playing against top opposition, the 13-year-old Fischer could only score 4½/11, tying for 8th–9th place. Yet he won the brilliancy prize for his game against International Master Donald Byrne, in which Fischer sacrificed his queen to unleash an unstoppable attack. Hans Kmoch called it "The Game of the Century", writing: "The following game, a stunning masterpiece of combination play performed by a boy of 13 against a formidable opponent, matches the finest on record in the history of chess prodigies". According to Frank Brady, "'The Game of the Century' has been talked about, analyzed, and admired for more than fifty years, and it will probably be a part of the canon of chess for many years to come." "In reflecting on his game a while after it occurred, Bobby was refreshingly modest: 'I just made the moves I thought were best. I was just lucky.'"

In 1957, Fischer played a two-game match against former World Champion Max Euwe at New York, losing ½–1½. On the USCF's eleventh national rating list, published on May 5, 1957, Fischer was rated 2231—over 500 points higher than his rating a year before. This made him the country's youngest ever chess master up to that point.In July, he successfully defended his US Junior title, scoring 8½/9 at San Francisco. As a result of his strong tournament results, Fischer's rating went up to 2298, "making him among the top ten active players in the country". In August, he scored 10/12 at the US Open Chess Championship in Cleveland, winning on tie-breaking points over Arthur Bisguier. This made Fischer the youngest ever US Open Champion. He won the New Jersey Open Championship, scoring 6½/7. He then defeated the young Filipino master Rodolfo Tan Cardoso 6–2 in a New York match sponsored by Pepsi-Cola.

Wins first US title

Based on Fischer's rating and strong results, the USCF invited him to play in the 1957/58 US Championship.[84] The tournament included such luminaries as six-time US champion Samuel Reshevsky, defending US champion Arthur Bisguier, and William Lombardy, who in August had won the World Junior Championship. Bisguier predicted that Fischer would "finish slightly over the center mark". Despite all the predictions to the contrary, Fischer scored eight wins and five draws to win the tournament by a one-point margin, with 10½/13. Still two months shy of his 15th birthday, Fischer became the youngest ever US champion. Since the championship that year was also the US Zonal Championship, Fischer's victory earned him the title of International Master. Fischer's victory in the US Championship sent his rating up to 2626, making him the second highest rated player in the United States, behind only Reshevsky (2713), and qualified him to participate in the 1958 Portorož Interzonal, the next step toward challenging the World Champion.

Grandmaster, candidate, author

Bobby wanted to go to Moscow. At his pleading, "Regina wrote directly to the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, requesting an invitation for Bobby to participate in the World Youth and Student Festival. The reply—affirmative—came too late for him to go." Regina did not have the money to pay the airfare, but in the following year Fischer was invited onto the game show I've Got a Secret, where, thanks to Regina's efforts, the producers of the show arranged two round-trip tickets to the Soviet Union.

Once in Russia, Fischer was invited by the Soviet Union to Moscow, where International Master Lev Abramov would serve as a guide to Bobby and his sister, Joan.Upon arrival, Fischer immediately demanded that he be taken to the Moscow Central Chess Club, where he played speed chess with "two young Soviet masters", Evgeni Vasiukov and Alexander Nikitin, winning every game. Chess author V. I. Linder writes about the impression Fischer gave grandmaster Vladimir Alatortsev when he played blitz against the Soviet masters: "Back in 1958, in the Central Chess Club, Vladimir Alatortsev saw a tall, angular 15-year-old youth, who in blitz games, crushed almost everyone who crossed his path… Alatortsev was no exception, losing all three games. He was astonished by the play of the young American Robert Fischer, his fantastic self-confidence, amazing chess erudition and simply brilliant play! On arriving home, Vladimir said in admiration to his wife: 'This is the future world champion!'"

Fischer demanded to play against Mikhail Botvinnik, the reigning World Champion. When told that this was impossible, Fischer asked to play Keres. "Finally, Tigran Petrosian was, on a semi-official basis, summoned to the club …" where he played speed games with Fischer, winning the majority."When Bobby discovered that he wasn't going to play any formal games … he went into a not-so-silent rage", saying he was fed up "with these Russian pigs", which angered the Soviets who saw Fischer as their honored guest. It was then that the Yugoslavian chess officials offered to take in Fischer and Joan as early guests to the Interzonal. Fischer took them up on the offer, arriving in Yugoslavia to play two short training matches against masters Dragoljub Janošević and Milan Matulović. Fischer drew both games against Janošević and then defeated Matulović in Belgrade by 2½–1½.

At Portorož, Fischer was accompanied by Lombardy. The top six finishers in the Interzonal would qualify for the Candidates Tournament. Most observers doubted that a 15-year-old with no international experience could finish among the six qualifiers at the Interzonal, but Fischer told journalist Miro Radoicic, "I can draw with the grandmasters, and there are half-a-dozen patzers in the tournament I reckon to beat." Despite some bumps in the road and a problematic start, Fischer succeeded in his plan: after a strong finish, he ended up with 12/20 (+6−2=12) to tie for 5th–6th. The Soviet grandmaster Yuri Averbakh observed,

In the struggle at the board this youth, almost still a child, showed himself to be a full-fledged fighter, demonstrating amazing composure, precise calculation and devilish resourcefulness. I was especially struck not even by his extensive opening knowledge, but his striving everywhere to seek new paths. In Fischer's play an enormous talent was noticeable, and in addition one sensed an enormous amount of work on the study of chess.

Soviet grandmaster David Bronstein said of Fischer's time in Portorož: "It was interesting for me to observe Fischer, but for a long time I couldn't understand why this 15-year-old boy played chess so well". Fischer became the youngest person ever to qualify for the Candidates and the youngest ever grandmaster at 15 years, 6 months, 1 day. "By then everyone knew we had a genius on our hands."

Before the Candidates' Tournament, Fischer won the 1958/59 US Championship (scoring 8½/11). He tied for third (with Borislav Ivkov) in Mar del Plata (scoring 10/14), a half-point behind Luděk Pachman and Miguel Najdorf. He tied for 4th–6th in Santiago (scoring 7½/12) behind Ivkov, Pachman, and Herman Pilnik.

At the Zürich International Tournament, spring 1959, Fischer finished a point behind future World Champion Mikhail Tal and a half-point behind Yugoslavian grandmaster Svetozar Gligorić.

Although Fischer had ended his formal education at age 16, dropping out of Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn, he subsequently taught himself several foreign languages so he could read foreign chess periodicals. According to Latvian chess master Alexander Koblencs, even he and Tal could not match the commitment that Fischer had made to chess. Recalling a conversation from the tournament: "'Tell me, Bobby,' Tal continued, 'what do you think of the playing style of Larissa Volpert?' 'She's too cautious. But you have another girl, Dmitrieva. Her games do appeal to me!' Here we were left literally open-mouthed in astonishment. Misha and I have looked at thousands of games, but it never even occurred to us to study the games of our women players. How could we find the time for this?! Yet Bobby, it turns out, had found the time!'"

Until late 1959, Fischer "had dressed atrociously for a champion, appearing at the most august and distinguished national and international events in sweaters and corduroys." Now, encouraged by Pal Benko to dress more smartly, Fischer "began buying suits from all over the world, hand-tailored and made to order." He told journalist Ralph Ginzburg that he had 17 hand-tailored suits and that all of his shirts and shoes were handmade.

At the age of 16, Fischer finished equal fifth out of eight at the 1959 Candidates Tournament in Bled/Zagreb/Belgrade, Yugoslavia, scoring 12½/28. He was outclassed by tournament winner Tal, who won all four of their individual games. That year, Fischer released his first book of collected games: Bobby Fischer's Games of Chess, published by Simon & Schuster.

Drops out of school

Fischer's interest in chess became more important than schoolwork, to the point that "by the time he reached the fourth grade, he'd been in and out of six schools." In 1952, Regina got Bobby a scholarship (based on his chess talent and "astronomically high IQ") to Brooklyn Community Woodward. Fischer later attended Erasmus Hall High School at the same time as Barbra Streisand and Neil Diamond. In 1959, its student council awarded him a gold medal for his chess achievements. The same year, Fischer dropped out of high school when he turned 16, the earliest he could legally do so. He later explained to Ralph Ginzburg, "You don't learn anything in school."

When Fischer was 16, his mother moved out of their apartment to pursue medical training. Her friend Joan Rodker, who had met Regina when the two were "idealistic communists" living in Moscow in the 1930s, believes that Fischer resented his mother for being mostly absent as a mother, a communist activist and an admirer of the Soviet Union and that this led to his hatred for the Soviet Union. In letters to Rodker, Fischer's mother states her desire to pursue her own "obsession" of training in medicine and writes that her son would have to live in their Brooklyn apartment without her: "It sounds terrible to leave a 16-year-old to his own devices, but he is probably happier that way". The apartment was on the edge of Bedford-Stuyvesant, a neighborhood that had one of the highest homicide and general crime rates in New York City. Despite the alienation from her son, Regina, in 1960, protested the practices of the American Chess Foundation[ and staged a five-hour protest in front of the White House, urging President Dwight D. Eisenhower to send an American team to that year's chess Olympiad (set for Leipzig, East Germany, behind the Iron Curtain) and to help support the team financially.

Olympiads

Fischer refused to play in the 1958 Munich Olympiad when his demand to play first board ahead of Samuel Reshevsky was rejected. Some sources claim that 15-year-old Fischer was unable to arrange leave from attending high school.Fischer later represented the United States on first board at four Men's Chess Olympiads, winning two individual Silver and one individual Bronze medals:

OlympiadIndividual resultPercentage

Leipzig 196013/18 (Bronze)

Varna 196211/17 (Eighth)

Havana 196615/17 (Silver)

Siegen 197010/13 (Silver)

Out of four Men's Chess Olympiads, Fischer scored +40−7=18, for 49/65: 75.4%. In 1966, Fischer narrowly missed the individual gold medal, scoring 88.23% to World Champion Tigran Petrosian's 88.46%. He played four games more than Petrosian, faced stiffer opposition,[170] and would have won the gold if he had accepted Florin Gheorghiu's draw offer, rather than declining it and suffering his only loss.

At the 1962 Varna Olympiad, Fischer predicted that he would defeat Argentinian GM Miguel Najdorf in 25 moves. Fischer actually did it in 24, becoming the only player to beat Najdorf in the tournament. Ironically, Najdorf lost the game while employing the very opening variation named after him: the Sicilian Najdorf.

Fischer had planned to play for the US at the 1968 Lugano Olympiad, but backed out when he saw the poor playing conditions.Both former World Champion Tigran Petrosian and Belgian-American International Master George Koltanowski, the leader of the American team that year, felt that Fischer was justified in not participating in the Olympiad. According to Lombardy, Fischer's non-participation was due to Reshevsky's refusal to yield first board.

1960–61

In 1960, Fischer tied for first place with Soviet star Boris Spassky at the strong Mar del Plata Tournament in Argentina, winning by a two-point margin, scoring 13½/15 (+13−1=1), ahead of David Bronstein.[179] Fischer lost only to Spassky; this was the start of their lifelong friendship.

Fischer experienced the only failure in his competitive career at the Buenos Aires Tournament (1960), finishing with 8½/19 (+3−5=11), far behind winners Viktor Korchnoi and Samuel Reshevsky with 13/19. According to Larry Evans, Fischer's first sexual experience was with a girl to whom Evans introduced him during the tournament. Pal Benko says that Fischer did horribly in the tournament "because he got caught up in women and sex. Afterwards, Fischer said he'd never mix women and chess together, and kept the promise."[185] Fischer concluded 1960 by winning a small tournament in Reykjavík with 4½/5, and defeating Klaus Darga in an exhibition game in West Berlin.

In 1961, Fischer started a 16-game match with Reshevsky, split between New York and Los Angeles. Reshevsky, 32 years Fischer's senior, was considered the favorite, since he had far more match experience and had never lost a set match. After 11 games and a tie score (two wins apiece with seven draws), the match ended prematurely due to a scheduling dispute between Fischer and match organizer and sponsor Jacqueline Piatigorsky. Reshevsky was declared the winner, by default, and received the winner's share of the prize fund.

Fischer was second in a super-class field, behind only former World Champion Tal, at Bled, 1961. Yet, Fischer defeated Tal head-to-head for the first time in their individual game, scored 3½/4 against the Soviet contingent, and finished as the only unbeaten player, with 13½/19 (+8−0=11).

1962: success, setback, accusations of collusion

Fischer won the 1962 Stockholm Interzonal by a 2½-point margin,going undefeated, with 17½/22 (+13−0=9). He was the first non-Soviet player to win an Interzonal since FIDE instituted the tournament in 1948.Russian grandmaster Alexander Kotov said of Fischer:

I have discussed Fischer's play with Max Euwe and Gideon Stahlberg. All of us, experienced 'tournament old-timers', were surprised by Fischer's endgame expertise. When a young player is good at attacking or at combinations, this is understandable, but a faultless endgame technique at the age of 19 is something rare. I can recall only one other player who at that age was equally skillful at endgames – Vasily Smyslov.

Fischer's victory made him a favorite for the Candidates Tournament in Curaçao. Yet, despite his result in the Interzonal, Fischer only finished fourth out of eight with 14/27 (+8−7=12), far behind Tigran Petrosian (17½/27), Efim Geller, and Paul Keres (both 17/27). Tal fell very ill during the tournament, and had to withdraw before completion. Fischer, a friend of Tal, was the only contestant who visited him in the hospital

Accuses Soviets of collusion

Following his failure in the 1962 Candidates,[d] Fischer asserted in a Sports Illustrated article, that three of the five Soviet players (Tigran Petrosian, Paul Keres, and Efim Geller) had a prearranged agreement to quickly draw their games against each other in order to conserve their energy for playing against Fischer. It is generally thought that this accusation is correct. Fischer stated that he would never again participate in a Candidates' tournament, since the format, combined with the alleged collusion, made it impossible for a non-Soviet player to win. Following Fischer's article, FIDE, in late 1962, voted to implement a radical reform of the playoff system, replacing the Candidates' tournament with a format of one-on-one knockout matches; the format that Fischer would dominate in 1971.

Fischer defeated Bent Larsen in a summer 1962 exhibition game in Copenhagen for Danish TV. Later that year, Fischer beat Bogdan Śliwa in a team match against Poland in Warsaw.

In the 1962/63 US Championship, Fischer lost to Edmar Mednis in round one. It was his first loss ever in a US Championship. Bisguier was in excellent form, and Fischer caught up to him only at the end. Tied at 7–3, the two met in the final round. Bisguier stood well in the middlegame, but blundered, handing Fischer his fifth consecutive US championship.

Semi-retirement in the mid-1960s

Influenced by ill will over the aborted 1961 match against Reshevsky, Fischer declined an invitation to play in the 1963 Piatigorsky Cup tournament in Los Angeles, which had a world-class field. He instead played in the Western Open in Bay City, Michigan, which he won with 7½/8. In August–September 1963, Fischer won the New York State Championship at Poughkeepsie, with 7/7, his first perfect score, ahead of Arthur Bisguier and James Sherwin.

In the 1963/64 US Championship, Fischer achieved his second perfect score, this time against the top-ranked chess players in the country. This result brought Fischer heightened fame, including a profile in Life magazine. Sports Illustrated diagrammed each of the 11 games in its article, "The Amazing Victory Streak of Bobby Fischer". Such extensive chess coverage was groundbreaking for the top American sports magazine. His 11–0 win in the 1963/64 Championship is the only perfect score in the history of the tournament, and one of about ten perfect scores in high-level chess tournaments ever. David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld called it "the most remarkable achievement of this kind". Fischer recalls:[220] "Motivated by my lopsided result (11–0!), Dr. [Hans] Kmoch congratulated [Larry] Evans (the runner up) on 'winning' the tournament… and then he congratulated me on 'winning the exhibition'."

Fischer's 21-move victory against Robert Byrne won the brilliancy prize for the tournament. Byrne wrote:

The culminating combination is of such depth that, even at the very moment at which I resigned, both grandmasters who were commenting on the play for the spectators in a separate room believed I had a won game!

International Master Anthony Saidy recalled his last round encounter with the undefeated Fischer:

Going into the final game I certainly did not expect to upset Fischer. I hardly knew the opening but played simply, and he went along with the scenario, opting for a N-v-B [i.e., Knight vs. Bishop] endgame with a minimal edge. In the corridor, Evans said to me, "Good. Show him we're not all children."

At adjournment, Saidy saw a way to force a draw, yet "sealed a different, wrong move", and lost. "Chess publications around the world wrote of the unparalleled achievement. Only Bent Larsen, always a Fischer detractor, was unimpressed: 'Fischer was playing against children'".

Fischer, eligible as US Champion, decided against his participation in the 1964 Amsterdam Interzonal, taking himself out of the 1966 World Championship cycle,[224] even after FIDE changed the format of the eight-player Candidates Tournament from a round-robin to a series of knockout matches, which eliminated the possibility of collusion.[214] Instead, Fischer embarked on a tour of the United States and Canada from February through May, playing a simultaneous exhibition, and giving a lecture in each of more than 40 cities. He had a 94% winning percentage over more than 2,000 games. Fischer declined an invitation to play for the US in the 1964 Olympiad in Tel Aviv.

Successful return

Fischer wanted to play in the Capablanca Memorial Tournament in Havana in August and September 1965. Since the State Department refused to endorse Fischer's passport as valid for visiting Cuba, he proposed, and the tournament officials and players accepted, a unique arrangement: Fischer played his moves from a room at the Marshall Chess Club, which were then transmitted by teleprinter to Cuba.Luděk Pachman observed that Fischer "was handicapped by the longer playing session resulting from the time wasted in transmitting the moves, and that is one reason why he lost to three of his chief rivals." The tournament was an "ordeal" for Fischer, who had to endure eight-hour and sometimes even twelve-hour playing sessions.[234] Despite the handicap, Fischer tied for second through fourth places, with 15/21 (+12−3=6), behind former World Champion Vasily Smyslov, whom Fischer defeated in their individual game. The tournament received extensive media coverage.

In December, Fischer won his seventh US Championship (1965), with the score of 8½/11 (+8−2=1),[238] despite losing to Robert Byrne and Reshevsky in the eighth and ninth rounds.[239][240] Fischer also reconciled with Mrs. Piatigorsky, accepting an invitation to the very strong second Piatigorsky Cup (1966) tournament in Santa Monica. Fischer began disastrously and after eight rounds was tied for last with 3/8. He then staged a strong comeback, scoring 7/8 in the next eight rounds. In the end, World Chess Championship finalist Boris Spassky edged him out by a half point, scoring 11½/18 to Fischer's 11/18 (+7−3=8).

Now aged 23, Fischer would win every match or tournament he completed for the rest of his life.

Fischer won the US Championship (1966/67) for the eighth and final time, ceding only three draws (+8−0=3), In March–April and August–September, Fischer won strong tournaments at Monte Carlo, with 7/9 (+6−1=2), and Skopje, with 13½/17 (+12−2=3). In the Philippines, Fischer played nine exhibition games against master opponents, scoring 8½/9.

Withdrawal while leading Interzonal

Fischer's win in the 1966/67 US Championship qualified him for the next World Championship cycle.

At the 1967 Interzonal, held at Sousse, Tunisia, Fischer scored 8½ points in the first 10 games, to lead the field. His observance of the Worldwide Church of God's seventh-day Sabbath was honored by the organizers, but deprived Fischer of several rest days, which led to a scheduling dispute, causing Fischer to forfeit two games in protest and later withdraw, eliminating himself from the 1969 World Championship cycle. Communications difficulties with the highly inexperienced local organizers were also a significant factor, since Fischer knew little French and the organizers had very limited English. No one in Tunisian chess had previous experience running an event of this stature.

Since Fischer had completed fewer than half of his scheduled games, all of his results were annulled, meaning players who had played Fischer had those games cancelled, and the scores nullified from the official tournament record.

Second semi-retirement

In 1968, Fischer won tournaments at Netanya, with 11½/13 (+10−0=3), and Vinkovci, with 11/13 (+9−0=4), by large margins. Fischer then stopped playing for the next 18 months, except for a win against Anthony Saidy in a 1969 New York Metropolitan League team match. That year, Fischer (assisted by grandmaster Larry Evans) released his second book of collected games: My 60 Memorable Games, published by Simon & Schuster. The book "was an immediate success".

1969–1972: World Champion

In 1970, Fischer began a new effort to become World Champion. His dramatic march toward the title made him a household name and made chess front-page news for a time. He won the title in 1972, but forfeited it three years later.

Road to the World Championship

Fischer's scoresheet from his round 3 game against Miguel Najdorf in the 1970 Chess Olympiad in Siegen, Germany

The 1969 US Championship was also a zonal qualifier, with the top three finishers advancing to the Interzonal. Fischer, however, had sat out the US Championship because of disagreements about the tournament's format and prize fund. Benko, one of the three qualifiers, agreed to give up his spot in the Interzonal in order to give Fischer another shot at the World Championship; Lombardy, who would have been "next in line" after Benko, did the same.

In 1970 and 1971, Fischer "dominated his contemporaries to an extent never seen before or since".

Before the Interzonal, in March and April 1970, the world's best players competed in the USSR vs. Rest of the World match in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, often referred to as "the Match of the Century". There was much surprise when Fischer decided to participate.

With Evans as his second,[268] Fischer flew to Belgrade with the intention of playing board one for the rest of the world. Danish grandmaster Bent Larsen, however, due to his recent tournament victories, demanded to play first board instead of Fischer, even though Fischer had the higher Elo rating. To the surprise of everyone, Fischer agreed. Although the USSR team eked out a 20½–19½ victory, "On the top four boards, the Soviets managed to win only one game out of a possible sixteen. Bobby Fischer was the high scorer for his team, with a 3–1 score against Petrosian (two wins and two draws)." "Fischer left no doubt in anyone's mind that he had put his temporary break from the tournament circuit to good use. Petrosian was almost unrecognizable in the first two games, and by the time he had collected himself, although pressing his opponent, he could do no more than draw the last two games of the four-game set".

After the USSR versus the Rest of the World Match, the unofficial World Championship of Lightning Chess (5-minute games) was held at Herceg Novi. "[The Russians] figured on teaching Fischer a lesson and on bringing him down a peg or two". Petrosian and Tal were considered the favorites, but Fischer overwhelmed the super-class field with 19/22 (+17−1=4), far ahead of Tal (14½), Korchnoi (14), Petrosian (13½), and Bronstein (13). Fischer lost only one game (to Korchnoi, who was also the only player to achieve an even score against him in the double round robin tournament). Fischer "crushed such blitz kings as Tal, Petrosian and Vasily Smyslov by a clean score". Tal marveled that, "During the entire tournament he didn't leave a single pawn en prise!", while the other players "blundered knights and bishops galore". For Lombardy, who had played many blitz games with Fischer, Fischer's 4½-point margin of victory "came as a pleasant surprise".

In April–May 1970, Fischer won at Rovinj/Zagreb with 13/17 (+10−1=6), by a two-point margin, ahead of Gligorić, Hort, Korchnoi, Smyslov, and Petrosian. In July–August, Fischer crushed the mostly grandmaster field at Buenos Aires, winning by a 3½-point margin, scoring 15/17 (+13−0=4). Fischer then played first board for the US Team in the 19th Chess Olympiad in Siegen, where he won an individual Silver medal, scoring 10/13 (+8−1=4), with his only loss being to World Champion Boris Spassky.[286] Right after the Olympiad, Fischer defeated Ulf Andersson in an exhibition game for the Swedish newspaper Expressen.Fischer had taken his game to a new level.

Fischer won the Interzonal (held in Palma de Mallorca in November and December 1970) with 18½/23 (+15−1=7),[289] far ahead of Larsen, Efim Geller, and Robert Hübner, with 15/23. Fischer finished the tournament with seven consecutive wins. Setting aside the Sousse Interzonal (which Fischer withdrew from while leading), Fischer's victory gave him a string of eight consecutive first prizes in tournaments. Former World Champion Mikhail Botvinnik was not, however, impressed by Fischer's results, stating: "Fischer has been declared a genius. I do not agree with this… In order to rightly be declared a genius in chess, you have to defeat equal opponents by a big margin. As yet he has not done this". Despite Botvinnik's remarks, "Fischer began a miraculous year in the history of chess".

In the 1971 Candidates matches, Fischer was set to play against Soviet grandmaster and concert pianist Mark Taimanov in the quarter-finals. The match began in mid-May in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Fischer was generally favored to win. Taimanov had reason to be confident. He was backed by the firm guidance of Botvinnik, who "had thoroughly analysed Fischer's record and put together a 'dossier' on him", from when he was in talks to play Fischer in a match "a couple of years earlier".[299] After Fischer defeated Taimanov in the second game of the match, Taimanov asked Fischer how he managed to come up with the move 12. N1c3, to which Fischer replied "that the idea was not his—he had come across it in the monograph by the Soviet master Alexander Nikitin in a footnote". Taimanov said of this: "It is staggering that I, an expert on the Sicilian, should have missed this theoretically significant idea by my compatriot, while Fischer had uncovered it in a book in a foreign language!" With the score at 4–0, in Fischer's favor, the fifth game adjournment was a sight to behold. Schonberg explains the scene

Taimanov came to Vancouver with two seconds, both grandmasters. Fischer was alone. He thought that the sight of Taimanov and his seconds was the funniest thing he had ever seen. There Taimanov and his seconds would sit, six hands flying, pocket sets waving in the air, while variations were being spouted all over the place. And there sat Taimanov with a confused look on his face. Just before resuming play [in the fifth game] the seconds were giving Taimanov some last-minute advice. When poor Taimanov entered the playing room and sat down to confront Fischer, his head was so full of conflicting continuations that he became rattled, left a Rook en prise and immediately resigned.

Fischer beat Taimanov by the score of 6–0.There was little precedent for such a lopsided score in a match leading to the World Championship.

Upon losing the final game of the match, Taimanov shrugged his shoulders, saying sadly to Fischer: "Well, I still have my music." As a result of his performance, Taimanov "was thrown out of the USSR team and forbidden to travel for two years. He was banned from writing articles, was deprived of his monthly stipend… [and] the authorities prohibited him from performing on the concert platform." "The crushing loss virtually ended Taimanov's chess career."

Fischer was next scheduled to play against Danish grandmaster Bent Larsen. "Spassky predicted a tight struggle: 'Larsen is a little stronger in spirit'" Before the match, Botvinnik had told a Soviet television audience:

It is hard to say how their match will end, but it is clear that such an easy victory as in Vancouver [against Taimanov] will not be given to Fischer. I think Larsen has unpleasant surprises in store for [Fischer], all the more since having dealt with Taimanov thus, Fischer will want to do just the same to Larsen and this is impossible.

Fischer beat Larsen by the identical score of 6–0. Robert Byrne writes: "To a certain extent I could grasp the Taimanov match as a kind of curiosity–almost a freak, a strange chess occurrence that would never occur again. But now I am at a loss for anything whatever to say… So, it is out of the question for me to explain how Bobby, how anyone, could win six games in a row from such a genius of the game as Bent Larsen". Just a year before, Larsen had played first board for the Rest of the World team ahead of Fischer, and had handed Fischer his only loss at the Interzonal. Garry Kasparov later wrote that no player had ever shown a superiority over his rivals comparable to Fischer's "incredible" 12–0 score in the two matches. Chess statistician Jeff Sonas concludes that the victory over Larsen gave Fischer the "highest single-match performance rating ever"

On August 8, 1971, while preparing for his last Candidates match with former World Champion Tigran Petrosian, Fischer played in the Manhattan Chess Club Rapid Tournament, winning with 21½/22 against a strong field.

Despite Fischer's results against Taimanov and Larsen, his upcoming match against Petrosian seemed a daunting task.Nevertheless, the Soviet government was concerned about Fischer."Reporters asked Petrosian whether the match would last the full twelve games… 'It might be possible that I win it earlier,' Petrosian replied",[318] and then stated: "Fischer's [nineteen consecutive] wins do not impress me. He is a great chess player but no genius." Petrosian played a strong theoretical novelty in the first game, gaining the advantage, but Fischer eventually won the game after Petrosian faltered. This gave Fischer a run of 20 consecutive wins against the world's top players (in the Interzonal and Candidates matches), a winning streak topped only by Steinitz's 25 straight wins in 1873–1882. Petrosian won the second game, finally snapping Fischer's streak.[324] After three consecutive draws, Fischer swept the next four games to win the match 6½–2½ (+5−1=3).Sports Illustrated ran an article on the match, highlighting Fischer's domination of Petrosian as being due to Petrosian's outdated system of preparation:

Fischer's recent record raises the distinct possibility that he has made a breakthrough in modern chess theory. His response to Petrosian's elaborately plotted 11th move in the first game is an example: Russian experts had worked on the variation for weeks, yet when it was thrown at Fischer suddenly, he faced its consequences alone and won by applying simple, classic principles.

Upon completion of the match, Petrosian remarked: "After the sixth game Fischer really did become a genius. I on the other hand, either had a breakdown or was tired, or something else happened, but the last three games were no longer chess." "Some experts kept insisting that Petrosian was off form, and that he should have had a plus score at the end of the sixth game …" to which Fischer replied, "People have been playing against me below strength for fifteen years." Fischer's match results befuddled Botvinnik: "It is hard to talk about Fischer's matches. Since the time that he has been playing them, miracles have begun." "When Petrosian played like Petrosian, Fischer played like a very strong grandmaster, but when Petrosian began making mistakes, Fischer was transformed into a genius."

Fischer gained a far higher rating than any player in history up to that time. On the July 1972 FIDE rating list, his Elo rating of 2785 was 125 points above (World No. 2) Spassky's rating of 2660.His results put him on the cover of Life magazine,[335] and allowed him to challenge World Champion Boris Spassky, whom he had never beaten (+0−3=2).

World Championship match

Fischer's career-long stubbornness about match and tournament conditions was again seen in the run-up to his match with Spassky. Of the possible sites, Fischer's first choice was Belgrade, Yugoslavia, while Spassky's was Reykjavík, Iceland. For a time it appeared that the dispute would be resolved by splitting the match between the two locations, but that arrangement failed. After that issue was resolved, Fischer refused to appear in Iceland until the prize fund was increased. London financier Jim Slater donated an additional US$125,000, bringing the prize fund up to an unprecedented $250,000 ($1.53 million today) and Fischer finally agreed to play.

Before and during the match, Fischer paid special attention to his physical training and fitness, which was a relatively novel approach for top chess players at that time. Leading up to this match he conducted interviews with 60 Minutes and Dick Cavett explaining the importance of physical fitness in his preparation. He had developed his tennis skills to a good level, and played frequently during off-days in Reykjavík. He had also arranged for exclusive use of his hotel's swimming pool during specified hours, and swam for extended periods, usually late at night. According to Soviet grandmaster Nikolai Krogius, Fischer "was paying great attention to sport, and that he was swimming and even boxing …"

The match took place in Reykjavík from July to September 1972. Fischer was accompanied by William Lombardy; besides assisting with analysis,Lombardy may have played an important role in getting Fischer to play in the match and to stay in it. The match was the first to receive an American broadcast in prime time. Fischer lost the first two games in strange fashion: the first when he played a risky pawn-grab in a drawn endgame, the second by forfeit when he refused to play the game in a dispute over playing conditions. Fischer would likely have forfeited the entire match, but Spassky, not wanting to win by default, yielded to Fischer's demands to move the next game to a back room, away from the cameras, whose presence had upset Fischer. After that game, the match was moved back to the stage and proceeded without further serious incident. Fischer won seven of the next 19 games, losing only one and drawing eleven, to win the match 12½–8½ and become the 11th World Chess Champion.

The Cold War trappings made the match a media sensation.[350] It was called "The Match of the Century", and received front-page media coverage in the United States and around the world. Fischer's win was an American victory in a field that Soviet players – closely identified with and subsidized by the state – had dominated for the previous quarter-century. Kasparov remarked, "Fischer fits ideologically into the context of the Cold War era: a lone American genius challenges the Soviet chess machine and defeats it". Dutch grandmaster Jan Timman calls Fischer's victory "the story of a lonely hero who overcomes an entire empire".Fischer's sister observed, "Bobby did all this in a country almost totally without a chess culture. It was as if an Eskimo had cleared a tennis court in the snow and gone on to win the world championship".

Upon Fischer's return to New York, a Bobby Fischer Day was held. He was offered numerous product endorsement offers worth "at least $5 million" ($30.6 million today), all of which he declined. He appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated with American Olympic swimming champion Mark Spitz and also appeared on The Dick Cavett Show, as well as on a Bob Hope TV special Membership in the US Chess Federation doubled in 1972, and peaked in 1974; in American chess, these years are commonly referred to as the "Fischer Boom". This match attracted more worldwide interest than any chess championship before or since.

Forfeiture of title

Fischer was scheduled to defend his title in 1975 against Anatoly Karpov, who had emerged as his challenger. Fischer, who had played no competitive games since his World Championship match with Spassky, laid out a proposal for the match in September 1973, in consultation with FIDE official Fred Cramer. He made three principal (non-negotiable) demands:

-

The match continues until one player wins 10 games, draws not counting.

-

No limit to the total number of games played.

-

In case of a 9–9 score, the champion (Fischer) retains the title, and the prize fund is split equally.

A FIDE Congress was held in 1974 during the Nice Olympiad. The delegates voted in favor of Fischer's 10-win proposal, but rejected his other two proposals, and limited the number of games in the match to 36. In response to FIDE's ruling, Fischer sent a cable to Euwe on June 27, 1974:

As I made clear in my telegram to the FIDE delegates, the match conditions I proposed were non-negotiable. Mr. Cramer informs me that the rules of the winner being the first player to win ten games, draws not counting, unlimited number of games and if nine wins to nine match is drawn with champion regaining title and prize fund split equally were rejected by the FIDE delegates. By so doing FIDE has decided against my participation in the 1975 World Chess Championship. Therefore, I resign my FIDE World Chess Championship title. Sincerely, Bobby Fischer.

The delegates responded by reaffirming their prior decisions, but did not accept Fischer's resignation and requested that he reconsider. Many observers considered Fischer's requested 9–9 clause unfair because it would require the challenger to win by at least two games (10–8). Botvinnik called the 9–9 clause "unsporting". Korchnoi, David Bronstein, and Lev Alburt considered the 9–9 clause reasonable.

Due to the continued efforts of US Chess Federation officials, a special FIDE Congress was held in March 1975 in Bergen, Netherlands, in which it was accepted that the match should be of unlimited duration, but the 9–9 clause was once again rejected, by a narrow margin of 35 votes to 32. FIDE set a deadline of April 1, 1975, for Fischer and Karpov to confirm their participation in the match. No reply was received from Fischer by April 3. Thus, by default, Karpov officially became World Champion. In his 1991 autobiography, Karpov professed regret that the match had not taken place, and claimed that the lost opportunity to challenge Fischer held back his own chess development. Karpov met with Fischer several times after 1975, in friendly but ultimately unsuccessful attempts to arrange a match, since Karpov would never agree to play to 10.

Brian Carney opined in The Wall Street Journal that Fischer's victory over Spassky in 1972 left him nothing to prove, except that perhaps someone could someday beat him, and he was not interested in the risk of losing. He also opined that Fischer's refusal to recognize peers also allowed his paranoia to flower: "The world championship he won ... validated his view of himself as a chess player, but it also insulated him from the humanizing influences of the world around him. He descended into what can only be considered a kind of madness".

Bronstein felt that Fischer "had the right to play the match with Karpov on his own conditions". Korchnoi stated: