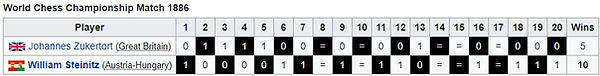

The full World Championship match results:

Get rythm (Joaquin Phoenix / Johnny Cash)

Hey get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

Get a rock and roll feelin' in your bones

Get taps on your toes and get gone

Get rhythm when you get the blues

A little shoeshine boy he never gets lowdown

But he's got the dirtiest job in town

Bendin' low at the people's feet

On a windy corner of a dirty street

Well I asked him while he shined my shoes

How'd he keep from gettin' the blues

He grinned as he raised his little head

He popped his shoeshine rag and then he said

Get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

Yes a jumpy rhythm makes you feel so fine

It'll shake all your troubles from your worried mind

Get rhythm when you get the blues

Get rhythm when you get the blues

Get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

Get a rock and roll feelin' in your bones

Get taps on your toes and get gone

Get rhythm when you get the blues

Well I sat and listened to the sunshine boy

I thought I was gonna jump with joy

He slapped on the shoe polish left and right

He took his shoeshine rag and he held it tight

He stopped once to wipe the sweat away

I said you mighty little boy to be a workin' that way

He said I like it with a big wide grin

Kept on a poppin' and he'd say it again

Get rhythm when you get the blues

C'mon get rhythm when you get the blues

It only cost a dime just a nickel a shoe

It does a million dollars worth of good for you

Get rhythm when you get the blues

For the good times (Kris Kristofferson)

Don't look so sad. I know it's over

But life goes on and this world keeps on turning

Let's just be glad we had this time to spend together

There is no need to watch the bridges that we're burning

Lay your head upon my pillow

Hold your warm and tender body close to mine

Hear the whisper of the raindrops

Blow softly against my window

Make believe you love me one more time

For the good times

I'll get along; you'll find another,

And I'll be here if you should find you ever need me.

Don't say a word about tomorrow or forever,

There'll be time enough for sadness when you leave me.

Lay your head upon my pillow

Hold your warm and tender body Close to mine

Hear the whisper of the raindrops

Blow softly against my window

Make believe you love me

One more time

For the good times

STABELVOLLEN MEDIA

Copyright of all music videoes, guest photoes and artworks solely belongs to the artists. Copyright of all other resources : Stabelvollen Media.

L O F T I N G II - ARTIKLER OG VIDEOER

THE BASICS OF LOFTING (c) Sandy Point Boat Works

Introduction

The correct term for one who lofts is a loftsman. This person is defined as one who creates patterns or frames. For the purposes of this document, I will refer to this person as a lofter.

I admit that lofting is something that I take for granted, simply because I know how. What seems simple to me now was once a mystery and a frustrating one at that. It seemed like every book I read left just enough out to keep me scratching my head. Like any good puzzle, if you look at enough pieces the picture starts to come into focus. over the last 25 years or so I have undoubtedly lofted a couple of hundred boats some were for packaged plans, some were for customers, some were just for fun.

The basic problem with getting information on lofting seems to me to be an issue of the times. When I purchase a modern boat building book, the section on lofting seems to be a bit light on information as to the specifics of their lofting technique. The omitted baseline information or stem configuration or any other number of small details seem to be the norm. It is also a sign of the times that most of the boat building books of the day are written and distributed by people who have business that sell plans and patterns for the same boats in the book. My cynical mind tells me that one has something to do with the other. On the other hand, there are some excellent boat building books which have chapters on lofting, however most of them are going on 60 or so years old and few but us hard core boat building junkies still read them. These books go back to the golden age of wooden boat building when seeing a home built boat on the water was at least as prevalent as a "store bought boat". The only issue that I find with these books is that some of the examples given within the text is typically more involved than the home builder will get involved with.

Becoming competent at lofting will open up an entire world of boat designs that would not otherwise be available to you. The best example I can give of this is boat building magazines of the last hundred years or so where it seems like countless tables of offsets ( also called lofting tables) for historic and geographically specific boats were given. Most of these boats excellent in both form and function and as good (in many cases better) than the boats you find today. I can't tell you how many times I see a "new" design which looks a whole lot like a design I have on my bookshelf from 50 years ago.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with taking an older design and making it new by lofting it and converting the building method to use new methods. Good boat designs were made to be built. 50 years ago, there was no epoxy, fiberglass was rare but coming on strong. Though I am not sure who invented epoxy, without a doubt, the Gougeon Brothers (founders of West System) did more to advance its use in the boat building world than anyone else I can think of. The onslaught of epoxy changed everything about boat building. Options for building a boat are now plentiful and at times confusing for the home builder. For example, a small rowing craft can be built in wood strip, stitch and glue, lapstrake, carvel planked or cloth over frame. Each boat coming from the same original design. The one thing they all have in common is they need to be lofted by somebody.

The History of Lofting (you need to know this)

There are a couple of things to know about lofting before you learn to loft. One fun fact is the origin of the term lofting. In days gone by (before computers), lofting needed to be done near the boat building effort as the builders needed to frequently check lines and measurements. Because the building site was both busy and dirty, lofting the boat on the building floor was far from perfect. Most of these boat shops did however have lofts in them where the drawing typically took place. You can probably see where we are going with this. The term of lofting originates from the location it was practiced.

The next thing you need to know is how the numbers are represented in a table of offsets. In the table of offsets you will typically see entries for half breadths, depths, profiles and sheers and they are represented by numbers that look something like this. 38-2+ or 3-2-2+. both of these number represent the same distance. they are 38 5/16". Offsets are read in either inches and eights with a plus sign indicated to add a 16th of an inch or feet, inches and eights with a plus sign for indicating an added 1/16". Typically it depended on the size of the boat as to whether or not feet were used and each designer has their own preference, both methods yield the same result.

If you are wondering how this method of lofting was settled on, it is simpler than you think. First, when boats began to be lofted, the imperial numbering system was most prevalent. The metric system, though invented in the late 17th century, was not adopted as a standard unit of measure by any country until 1795 when France adopted it as their standard measuring system. Great Britain and the United states which are arguably the two largest ship and boat building countries of the last 200 years did not adopt the metric system until the mid 1960's and in the U.S. it is typically only used in scientific fields. By that time many a boat had been designed, lofted and recorded and there is little urgency to change a system which has so much history and works so well. Remember that boat designs are not meant for one geographic area so unless someone gets the urge to re-loft and re-publish the thousands of boat plans already published, the system is in little danger of being toppled. More importantly, you would be doing yourself a disservice by not learning the measuring scheme as there are so many boat designs published using the system.

If you are wondering why the + sign for 16ths, it's simple, measuring devices were not accurate to a 16th of an inch in the 18th century, so they were happy with just saying "a little more than an 8th"

The Essential Terms

Many people get confused at where the line is between boat building and lofting and there is good reason for this, the two are interdependent. You cannot loft a boat without knowing something about boat building and you cannot build a boat unless someone has lofted it out first. As an example, you don't need to know how to mount a sheer clamp in order to loft, but you sure need to know what it is if you are going to loft it. Little wonder why pretty much all small craft lofters are also small boat builders.We will use some boatbuilding terms as we go, however the essential terms for lofting are actually very few.

We should start with the views. Boats are lofted in 3 dimensions, 2 dimensions at a time. There are 3 views, each view giving two dimensions. Each of these views could be mapped to the Cartesian coordinate system, however historically neither the X,Y or Z axis has been assigned to any view. In using newer CAD systems, however it is required to assign a planes to each view and I imagine that different designers assign different planes. When I loft,

- the frames view is the X-Y plane,

- the Profile view is the Y-Z view and

- the Plans view is the X-Z view.

Don't get too hung up on this concept as it is not even relevant unless you are using a computer to loft your boat and if you are using a CAD system, the concept is probably not foreign to you.

Now let's describe the views.

Lofting

Each boat design has a set of offsets and lines given in numerical form. These numbers correspond to measured distances from a reference point(s).

- Vertical distances are usually given (+ or -) from the waterline or

bottom of keel (BOK).

- Width distances are given from the centerline.

- Length is usually given from approx. the boats center.

Any point on the boat can be located by giving it's position using what are basically it's coordinates.

When lofting you basically lay out the transverse frames and the fore & aft lines full size.

The transom and other parts may be laid out also. This is usually done on a plywood or simularly smooth surface.

Nails are driven into the critical and called for points. By laying wooden battens (straight, long pieces of flexible wood) across these nails one can check for fairness. Critical errors will stand out clearly.

Frames and transverse bulkheads shape and size will be "lifted" from the lofted lines.

Plan view

This is the view of the boat looking down from the sky. traditionally the plan view has two halves. On one side you will see the lines of the boat. the lines in this view are the waterlines, the sheer, the centerline and the frame spacing if there is one. On the other side of the plans view you will see what is basically a sketch of the boat. This is where you will see the deck layout, seating, engine well or other materially important items the designer or lofter deems necessary to give the builder a perspective of the boat.

The Profile view

The profile is exactly what it sounds like. If the boat was suspended in mid air and you were looking at it from the side, you would be looking at the profile. So another way to say profile view is to call it a side view (but don't). In the profile view you will typically see

- the sheer line,

- the profile line (which is the line describing the bottom from the transom to the stem tip), and

- buttock lines.

The frames view

This is sometimes called the forms view. This view is the view of each sectional frame as viewed from the front or the rear of the boat. If the same boat were suspended in mid air and you were looking from the transom forward or the transom back you would be looking at the frame view. It is called the frame view as this is the view that is used to "pick" the frames from. That is to say it is the view which you can create patterns for the frames or building forms for your boat. If you know the size of the stock of the building frames (which should be on the boat plans), and you have the outline of the frames from the frames view, it becomes an easy task to create patterns for your frames. Each view has specific lines which need to be lofted in order to create an accurate view of the boat.

Assuming we are lofting a round bilged boat, the profile view needs to have 5 items lofted.

- The buttock lines,

- the sheer line,

- the profile line,

- the transom line and

- the stem line.

Some designers combine the profile line and the stem line, however they are typically not integrated as the stem of the boat needs to be transformed into a frame member unless you are building a stitch and glue hull.

- The sheer line (shown in green) is the line which describes the point at which the hull ends. At this line either the boat is terminated with a

gunwale or the deck begins. If there is a deck it is also lofted out as it will need support members.

- The profile line (shown in blue) is the bottom of the boat hull. There is a distinction between the bottom of the hull and the bottom of the boat.

There are items which extend past the hull bottom such as skegs and keels. Though these need to be lofted out for the building process, they

are not technically part of the hull lofting. These parts of the boats need not be described in the lofting table, though you may see them there as

part of the designers convenience. Typically they are described in the boat plans.

- The stem line (also shown in blue from first frame forward) is the curve described in the table of offsets which specifies the curve of the

stem from some given point on the profile line to the sheer line. The designer will give enough points in the table of offsets to accurately

manufacture a stem frame or what is more commonly simply called the stem.

- The buttock lines (shown in red) are lines which when viewed from the profile view appear to be slices of the hull which are parallel to the

centerline of the hull. These points in conjunction with the waterlines give enough information to fair all the curves.

- The Transom line (shown in Yellow) shows you the rake of the transom as well as a perspective which allows you to "extend" the transom if it

does not mount parallel to the rest of the boats frames. This also assumes that your boat is not a double ender or a boat with two stems.

Because the plan view is a different perspective, it stands to reason that we will be lofting different lines or in some cases, the same lines from a different perspective. Consider the sheer line. The sheer line is viewed in all three perspectives, the plan view, profile view and the form view. However, because we are observing the boat from three different planes of view, the information given from the sheer plotting in each perspective will give us different information.

- In the Plan view, the plot of the sheer line will show us how wide the boat is at the sheer line,

- in the profile view, the sheer line will show us how deep the boat is from the gunwales to the profile or the bottom of the boat. Finally,

- in the frames view we will see the compound curve from the stem to the transom or far stem.

The plans view lines

- The water lines shown in the graphic in purple act much as the

buttock lines only in a different perspective. The waterlines slice the

boat from the bottom to the top. Lofting the waterlines allows you to

ensure that the hull has no bulges or hollows at any intersection of the

hull from the gunwale lines to the bottom of the boat. Using the term

water line is a bit misleading. They are simply lines drawn up the hull

theoretically paralell with the actual water. In reality, an actual waterline

will depend on the amount of displacement not only of the hull but the

weight of the items in the boat at the time. As for them being paralell,

that again will depend on the dispersement of weight within the boat.

For the purpose of lofting, it is important to have mesurements

from some controlled and imovable base line, so in lofting,

the waterlines are actually lines moving up (or down if the boat is

being lofted upside down) the hull from the baseline.

The sheer line is lofted which will give you the breadth of the hull at any given point.

- Finally, if your boat has a transom, the transom lines will also be lofted in this view showing the length of the hull at both the sheer line and

bottom of the hull as well as the transom breadth at any given waterline. If the transom sits at a 90 degree angle with no rake, these there

will only be one line.

The frames view

For me, this is the view which tells the entire picture. All of the lines are lofted in this view. The water lines and the buttock lines appear as a grid in this view, however each frame or form is lofted in this view. The frames are slices of the boat at given intervals starting at the transom and working forward to the stem of the boat. If your boat is a double ender then the stern of the boat is a point just as the stem in this view is a point indicating the place where the sheer line meets the profile line.

This boat has a transom with a good bit of rise aft. If you look again at the waterlines in the plans view, you will see that as the water lines get lower on the boat, they turn in on the hull. If you look at the frames drawing on the left, you will see that the lowest water line never reaches the transom. There is one more set of lines that we should discuss. they are called diagonals. Diagonals are typically only drawn in the frames view and serve the specific purpose of filling in the blanks. They are not necessary for the lofting of the boat, however, depending on the hull shape, they are necessary for picking off points to create frames. They are also at times lofted in the plans view just as another verification of a fair shape to the hull, however little information other than that can be derived from their lofting in this view. Because of the curves of some hull shapes, the water lines and buttock lines can sometimes leave blind spots on various frame locations. These lines are defined as starting at an arbitrary point typically above the boat on the centerline and a second point given for each diagonal usually defined as an intersection of a water line and buttock line. however, at least as far as this lofter is aware, any rules for the defining of the two points necessary for the diagonals. They simply need to accomplish the need to fill in points on the frames that are not otherwise defined by the waterlines or diagonals.

Boat building vs Boat Lofting

That pretty much describes all of the components to a lofted boat. Now I know that you may be thinking, but what about the gunwales, knees, keels, keelson, battens etc, etc, etc.......

I told you in the beginning of this that there is a difference between boat building and lofting. Lofting is an effort to define a hull. the rest of the stuff is about how the boat is built and what is needed to make that happen.

Before you jump all over me for that statement, let me give a couple of examples.

If you are lofting a boat stem, are you lofting it for a Laminated split stem which has an inner and outer stem, or are you using a traditional stem with a stem foot and sawn lumber. Is the stem on piece so that you need to loft the rabbet line? Or is this a stitch and glue boat in which case you don't need to loft the stem piece at all because there isn't one.

So understand what I am saying here. I am not saying that a good lofter will not be able to both draw and pick off such items as stem details, , batten locations, transom knees and so forth. What I am saying is that these things are not necessary for the purposes of defining the hull shape and for picking off the patterns for the molds or frames, which of course is the job of the lofter. Once the hull shape is defined, and presuming that you know how the boat is to be built or at least the methodology which will be used to build the boat, then you can add such detail to the drawings as to convey instructions to the perspective builders. In the case of a plank on frame boat you will want to add battens, knees, stem configuration, transom framing, skeg, engine bedding, floor supports, bulkheads and on and on. In the case of a stitch and glue boat you will want to give panel expansions, bulkheads and their locations, specific locations of any structural members and seating arrangements which are typically all part of the structural integrity of a stitch and glue hull.

LOFTING : HOW TO LOFT A SIMPLE BOAT PLANav Karen Wales (ass. ed. WoodenBoat.) Illustrasjoner av Sam Manning.

Lofting

Lofting - enlarging a boat’s lines to full size—is an important part of boatbuilding. Having this skill opens the door to a wider variety of boats to build and to having better control over the construction process.

Some builders have a love-hate relationship with lofting, yet it pays us fourfold for our efforts. It allows us to make corrections (yes, even great designers can make a few mistakes), it helps us to better understand the designer’s plans, and it renders patterns from which we can build the boat. Additionally, it gives us some latitude in making changes, such as sweetening the sheerline or adding a bit more rake to the transom.

I have chosen the Asa Thomson skiff for my subject. This article will cover the basic steps required to loft this simple flat-bottomed boat.

The goal is to replicate, at full size, enough of the lines shown on the drawing so you can build the four station molds, the stem, and the transom.

Some very fine builders have tackled the subject of lofting.

Among them are Greg Rössel in his two-part article,

“Lofting Demystified” (WoodenBoat Nos. 110 and 111) and Sam Manning in his article, “Some Thoughts on Lofting” (WoodenBoat No. 11).

Both are rich in information but feature round-bottomed boats, which are more complex than the flat-bottomed skiff we will discuss here. I will reference these—and other works—as this article is intended as a primer to those writings and as a starting point for the first-time loftsman.

Lofting Tools and Supplies

-

Loft floor (board), two 4′ x 8′ sheets of 1/4″ plywood with one “A” face

-

Combination square

-

Long straightedge, 4′ or more

-

Batten, 3/4″ x 3/4″ x 14′, clear pine

-

Pick-up sticks, 3/32″ x 1″ x 3′

-

Chalkline, 16′ long

-

Some 2″ box nails

-

Light-duty hammer

-

Colored pencils and pencil sharpener

-

Erasers

-

Knee pads

-

Trammel points for swinging large radius arcs

Preparations and Procedures

Let’s look at the plan of the Asa Thomson skiff and see what we need to know to do our first lofting job. For convenience, this plan gives detailed construction information. The three main views are the profile, plan, and sections. The profile shows us the boat side-to in the upright position, the plan view shows the boat as if we were looking down on it, and the sections show the shape end-on, as if we sliced the boat like a loaf of bread. These three views are related in a deliberate and important way. Notice that a given point on the boat, say the sheer at station No. 2, has two dimensions in the profile view:

the fore-and-aft distance from station No. 0 and the height from the baseline to the designed waterline (DWL). The plan view shows the same fore-and-aft length as well as the width from the centerline.

The sections show the width from the centerline (CL) and the height from the baseline. Notice that the same dimension appears in two different views and that this dimension must be the same in both views. As you are lofting any boat, it is absolutely required that you keep any dimension the same in all views in which it appears.

This is known as keeping the lines dimensionally fair. The two lines that we will be lofting are the sheer and chine (or, in this case, the bottom).

Plan Conventions and Quirks

While most designers try to stick with certain conventions, sometimes it makes sense to break a rule or two—and sometimes rules are broken for no apparent reason. Here are a few of the conventions for drawn plans:

-

In the profile view, the bow is usually to the right.

-

Stations are usually equal divisions along the designed waterline, beginning from the right, or forward, end of the boat, and proceeding toward the left.

-

The body plan is composed of a half-section drawn for each station, the forward part of the hull on one side of the centerline and the aft opposite, on the other.

-

The standard layout is to show the profile view at the top, the body plan to the right of the profile, and the plan view aligned below the profile.

-

Offsets (sets of numbers that define the boat’s shape) are most often read in feet, inches, and eighths of an inch. So, 1–2–3 means 1′ 2 3⁄8″.

-

Plans can be drawn to either the inside or outside of the planking. If they are drawn to the outside of the planking, plank thickness must be deducted from the given dimensions when making the molds. If drawn to the inside of the planking, this extra step is not necessary.

These two lines define the outside shape of the skiff, and all other lines are derived from them. We will lay these two lines down at their full size on the loft floor using the dimensions given in the offset table.

Prepare the Lofting Floor

Your “loft floor” or “loft board” should be a couple of feet longer than the skiff and about one foot wider than its half-beam (half-width). Two 4′ x 8′ pieces of plywood laid end-to-end and fastened down to the shop floor will work well as a loft floor. Apply a few coats of shellac-based white or light gray primer to make your lines easier to see and to erase.

...

Trammels do the accurate work of full-sized layout in lofting. Their use as giant dividers helps avoid the mistakes made by misreading rulers.

To see deviations from these norms, we need look no further than the Asa Thomson skiff plan. First, her stations begin at the left (aft) end of the boat and proceed to the right. Next, her body plan is given in full section, rather than half section. In fact, two renderings are made, showing her forward sections and her aft sections separately. Finally, offsets for this plan read in feet, inches, and sixteenths of an inch.

These departures are not wrong. They are usually done for greater clarity. Since this is often a first-time builder’s project, these details are not excessive, and, diminutive boats like our skiff are best described with these more exacting offsets.

Every plan will display differences. Be sure to spend some hours studying your plan before jumping into the lofting process. It’s time well spent.

Lofting the Sheer and Chine

Let’s begin by lofting the sheerline in the profile view. This is generally the most prominent visual line on any boat, and we want to make sure it has eyesweet fairness.

Lay down the heights, as given in the table of offsets, for the sheer for each station and the endpoints at the transom and stem, each time starting from the baseline. Remember that these offsets read in feet, inches, and sixteenths of an inch. So, the point that defines the height of the sheer at station No. 1 is 1–9–3—that is, 1′ 9 3⁄16″. Mark that point in a clear, 90-degree intersection with the station line. Continue for each station, as well as the ends of the sheer at the transom and stem.

Profile and half-breadth views are normally superimposed on the lofting grid to save space and minimize error by measuring outward from (“offset” from) the same centerline/baseline and the station perpendiculars. The offset table corrals the governing measurements. The body plan, developed within these full-sized superimposed views, is usually laid out upon a scrive board easily moved to the construction site.

Next, lay the batten on the floor and, using 2″ box nails, set the batten at station No. 2. To do this, drive a nail into the plywood loft floor, next to the batten on the inside of the curve, as if giving it a place to lean. Don’t drive nails through the batten. Position the batten so the sheerline points can be seen on its convex (tensioned) side. This will help you see the batten and line when you later check for fairness. Next, fasten the batten in a similar fashion at the remaining points.

Letting the batten run straight beyond the two endpoints can introduce some unfairness. To prevent this, continue the curve of the batten beyond the endpoints of the boat and fasten it about 18″ from them.

Now comes the eye-sweet fairing. Get your eye right down on the floor and sight along the convex side of the batten, then stand back and sight along the batten again (see cover illustration). Is it smooth all the way along? If not, release a nail where you think the unfairness is and see what the batten does.

Alternatives to the Lofting Floor

Lofting was traditionally done on the floor of a boatshop’s loft. However, if you would rather not crawl on the floor, there are alternatives. Greg Rössel suggests stiffening the back of the loft board and setting it on sawhorses. Sam Manning likes to hang his loft board on his wall. Both methods spare the back and knees.

If it moves, the line was probably unfair at that spot. If not, refasten it and try the adjacent station. A good trick is to release each nail in order (except for the end ones), see if the batten moves, then refasten it.

It is common to see some small movement at some stations, say between 1⁄32″ and 1⁄8″. If the sweep of the batten is eye-sweet, trust it, as it wants to spring to a naturally fair curve. Then draw the line, pressing down on the batten between nails to keep it in position. I like to use colored pencils to help me discern the different views. Make sure that you clearly label each line with both its name and view (e.g., sheer–profile).

Repeat the process for the chine (bottom) in profile. Then, lay out the shape of the stem profile and transom using dimensions on the plan. In this case, the stem offsets aren’t shown on the plan (see illustration below). Because the transom slopes, its depth measurement is foreshortened and inaccurate in the half-breadth and the body plans.

Its true shape must be laid out in a separate loft view with width and depth taken as shown here with the sketched dividers. You are now ready to lay down the sheer and chine (bottom) in plan view. Start by laying out the half-breadth of the face of the inner stem as shown (see illustration). Note that this is 1″ aft of the profile view of the stem station line. The station widths are measured from the same line as the station heights, but in plan view, that line now becomes the centerline (CL). Continue, as before, laying out the half-breadths for each of the stations and the stem and transom for both the sheer and bottom. Then run the batten, check and adjust it if necessary for fairness, and draw the lines. In laying out the endings of the stem in plan view, remember to keep all dimensions dimensionally fair in every view. You can see that the fore-and-aft (longitudinal) positions of the top of the stem have to be the same in both the profile and plan views. In order to keep it absolutely the same in both views, use a “pick-up stick” to pick up this dimension in the profile view and transfer it to the plan view. This illustrates a basic rule of lofting: Once a dimension is laid down in one view, always pick it up from that view to transfer it to all other views. Do not revisit the table of offsets for this information.

The Body Plan

Now that the sheer and chine (bottom) are laid down and faired in both the profile and plan views, it is time to construct the body plan or sections from which the building molds will be patterned. You can lay these sections down on your plywood loft floor using a convenient section line for the centerline (CL) of the body plan, but you may find it less confusing to use a scrive board. This can be a sheet of plywood about a foot wider than the width of the skiff (about 5′ 6″ wide) and a foot greater in height (about 3′ 6″ ). A scrive board is handy when it’s time to make molds.

Strike a baseline on your scrive board, about 6″ from its bottom edge, and then construct a CL perpendicular to it from the baseline’s midpoint. Using pick-up sticks, transfer each station’s sheer and chine (bottom) locations to the body plan, and connect the points at each station with straight lines, remembering that the lines that represent the boat’s bottom are horizontal and square with the CL. On this boat, lines are drawn to the inside of the planking, so in making the molds there is no need to deduct plank thickness from our sections.

The basic lofting and fairing are now done, and it is time to make the building molds for each station. Transferring the lines to the mold stock is quick and easy.

Now that you understand the basics, you may want to learn more advanced techniques such as learning how to loft a round-bottomed boat. Before long, you’ll be developing curved, raked transoms with the best of ’em — and your building options will be many.

Laying Out the Lofting Grid

Lines are laid out on a right-angle grid. In order for your boat to be of the same dimensions and shape as the Asa Thomson skiff, your grid must be laid down accurately.

Starting the Grid Right

An inaccurate grid will cause errors that grow exponentially over the course of the project. Accuracy begins at the baseline. This line must be a continuous, straight line. Loftsmen of yore have used piano wire and turnbuckles for striking a baseline. Some loftsmen use a pair of ice picks to tension fishing line along their proposed line, and then set the head of a combination square so that it just kisses the line, make a series of marks along the line, and finally connect the dots. For our purposes, a chalkline, a long straightedge, and a steady hand will do nicely.

How to Lay Out the Lofting Grid

Start by snapping a chalkline about 6″ from the long edge of your plywood loft floor for its full length. Using a long straightedge, pencil in this line, which will serve as both the baseline in the profile view and the centerline (CL) in the plan view. This means that both the profile and plan views will be laid down on top of each other. It may seem a little confusing, but it saves a lot of space. Remember, in lofting, we enlarge the lines (i.e., the boat’s shape) for building purposes—we do not attempt to make enlarged, detailed construction drawings as found in the plans.

Once you have laid down an accurate baseline/centerline (CL), strike a perpendicular line about one-third of the way along the baseline. This will be station No. 2. To strike a perpendicular at station No. 2:

-

Sweep an arc across the baseline with compass or trammel points set outward from station No. 2 at arbitrary radius “a”

-

Sweep a second, longer arc of arbitrary radius “b” outward from the crossing points of “a.” For best accuracy, make “b” two or three-times longer than “a” (commensurate with keeping “b” on the loft floor

-

Draw a line upward from 2 through the crossing of the “b” arcs. This line is perpendicular to the baseline

ORD OG TERMER

boat lofting refererer til prosessen med å lage nøyaktige tegninger eller skisser av båtens form, vanligvis på en stor flate, for å planlegge

konstruksjonen av båten. Dette innebærer å overføre designet av båtens skrog til en større skala, ofte på gulvet eller en stor

arbeidsflate, hvor målingene og kurvene tegnes nøyaktig før man kutter ut materialene.

sheerline ripa, linjen som representerer båtens øverste kant langs skroget, fra baugen til akterenden, sett fra siden.

Dette er en viktig linje i båtbyggerens tegninger og skisser, og den viser hvordan båtens profil og høyde varierer langs lengden

på skroget.

Sheerline markerer dermed hvordan båtens øvre kant (ofte dekkets linje) er utformet, og kan ha betydning for båtens estetikk,

stabilitet og funksjonalitet. I lofting, når båtbyggeren skaper detaljerte tegninger på stor skala, vil sheerline ofte være en av

de første linjene som blir tegnet. Den er essensiell for å få båtens form riktig, og kan påvirke hvordan de andre linjene og

dimensjonene på skroget skal tegnes og kuttes.

transom akterspeil

rake rett skrå oppover mot høyre (stamnform)

skiff skip, båt

molds former

stem stamn, stevn

plywood kryssfiner

straightedge linjal

batten lekter

light-duty hammer lett hammer

knee pads knebeskyttere

trammel points passer (?)

upright position oppreist stilling

plan view planvisning

side-to sett fra siden

end-on sett fra endene

deliberate tilsiktet

sheer ripa, den linjen som representerer båtens øverste kant langs skroget, fra baugen til akterenden, sett fra siden.

waterline (WL) vannlinjen, linjen hvor båtens skrog møter vannflaten.

vannlinjen kan også referere til en hvilken som helst linje på båtens skrog som er parallell til vannflaten når båten flyter

i en jevnt trimmet posisjon. Derfor er vannlinjer en klasse av "skipslinjer" som brukes til å betegne formen på et skrog

i planene for marinearkitektur-linjer.

plan view horisontalplan-visning, med skjæringslinjer mellom båtens skrog og et vilkårlig plan parallelt ned vannoverflaten.

fore-and-aft length båtens fulle lengde, fra stamn til stamn

centerline (CL) båtens senterlinje, dvs. eiu rett linje gjennom stamnene

baseline basislinjen

keeping dimensionally fair keeping any dimensions the same in all views

chine line bunnlinjen, bunnen, se fig. ovenfor

LOFTING - VIDEOER fra Smithy's Boatshed, Chasegamingtv og Boat building Academy

(c) Rettighetshaverne nevnt ovenfor har full copyright til videoene. Stabelvollen Media har ikke rettigheter til videoene, som kun er tatt med for å fremme kunnskap om lofting

innenfor klinkerbåt tradisjonen.

(c) The rights holders mentioned above have full copyright to the videos. Stabelvollen Media does not have rights to the videos, which are only included to promote knowledge

about lofting within the clinker boat tradition.

Traditional Clinker Boatbuilding av Smithy's Boatshed - Episode 1 - 7

Episode 1 Traditional clinker Construction

Episode 3 Traditional clinker Construction

Episode 5 Traditional clinker Construction

Episode 2 Traditional clinker Construction

Episode 4 Traditional clinker Construction

Episode 6 Traditional clinker Construction

Episode 7 Traditional clinker Construction

(c) Smithy's Boatshed

2D plans for 3D ships 1 - 6 av chasegamingtv@gmail.com

1. Interpreting Lines Plans

2. Key Lines

3. Curvw Lines

4. Water Lines

5. Body Plan

6. Modelling

Lofting 101 Introduction to Lofting av Boat building Academy

- Drawing a grid

- Profile view

- Station Lines

Lofting 101-2 Introduction to Lofting av Boat building Academy

Ep2 - We Build a Lofting Stage (Boat Plans and Lofting)

Lofting 101-1 Introduction to Lofting av Boat building Academy

- What is a Table of Offsets and Lofting? Designing a boat.

Lofting 101-3 Introduction to Lofting av Boat building Academy

Ep3 - We Build a Lofting Stage (Boat Plans and Lofting)

(c) Rettighetshaverne nevnt ovenfor har full copyright til videoene. Stabelvollen Media har ikke rettigheter til videoene, som kun er tatt med for å fremme kunnskap om lofting

innenfor klinkerbåt tradisjonen.

REFERANSER OG LINKER

Sandy Point Boat Works:

Wodden Boat:

Smithy's Boatshed:

Boat Building Academy:

https://sandypointboatworks.com/boat-building-articles-journals/boat-building-articles/lofting-basics

https://www.youtube.com/user/OrcaBoats

https://skills.woodenboat.com/guides/lofting-how-to-loft-a-simple-boat-plan/